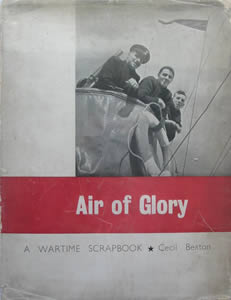

Air of Glory – A Wartime Scrapbook by Cecil Beaton

“Be daring, be different, be impractical, be anything that will assert integrity of purpose and imaginative vision against the play-it-safers, the creatures of the commonplace, the slaves of the ordinary.” - Cecil Beaton

“Be daring, be different, be impractical, be anything that will assert integrity of purpose and imaginative vision against the play-it-safers, the creatures of the commonplace, the slaves of the ordinary.” - Cecil Beaton

Sir Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton CBE, was a British fashion and portrait photographer, diarist, interior designer and an Academy Award-winning stage and costume designer for films and the theatre. Admitted to the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1970, (founded by ‘fashionista’ Eleanor Lambert in 1940 as an attempt to boost the reputation of American fashion at the time), Beaton’s flamboyant personality and flair for style resulted in his being credited for more or less inventing the ‘Edwardian look’ with ‘My Fair Lady’ for which he designed both the sets and costumes. As David Bailey remarks:

Sir Cecil Walter Hardy Beaton CBE, was a British fashion and portrait photographer, diarist, interior designer and an Academy Award-winning stage and costume designer for films and the theatre. Admitted to the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1970, (founded by ‘fashionista’ Eleanor Lambert in 1940 as an attempt to boost the reputation of American fashion at the time), Beaton’s flamboyant personality and flair for style resulted in his being credited for more or less inventing the ‘Edwardian look’ with ‘My Fair Lady’ for which he designed both the sets and costumes. As David Bailey remarks:

“Nobody really looked like that in Edwardian times but now everyone thinks they did. He made it fantastically stylish.”

Cecil Beaton was born on 14th January 1904 in Hampstead to Ernest Walter Hardy Beaton, a successful timber merchant, and his wife Etty Sissons. Cecil’s grandfather, Walter Hardy Beaton had founded the family business ‘Beaton Brothers Timber Merchants and Agents’, into which Cecil’s father, Ernest, duly entered. Ernest Beaton was also an amateur actor and had met Etty, who had come to London to visit her sister, when playing the lead in a play. One of four children, Cecil was educated at Heath Mount School (where, it is widely believed, he was bullied by Evelyn Waugh) and St Cyprian's School, Eastbourne, where his artistic talent was quickly recognised. Beaton nursed an early fascination for clothes, appearances and stylish things and as he was growing up his nanny began teaching him the basics of photography and developing film using a Kodak 3A Folding Camera - a model which was renowned at the time for being an ideal piece of equipment on which to learn . He would often get his sisters and mother to sit for him and once he was sufficiently proficient, he would send the photos off to London society magazines, often writing under a pen name and ‘recommending’ the work of one Cecil Beaton!

After attending Harrow School and St. John’s College Cambridge, where he studied history, art and architecture; it was through university contacts that Beaton had his first ever photograph published. It was of the literary scholar and theatre director George ‘Dadie’ Rylands – a portrait sitting for his ‘Duchess of Malfi’. Vogue Magazine bought and printed what Beaton himself later described as:

After attending Harrow School and St. John’s College Cambridge, where he studied history, art and architecture; it was through university contacts that Beaton had his first ever photograph published. It was of the literary scholar and theatre director George ‘Dadie’ Rylands – a portrait sitting for his ‘Duchess of Malfi’. Vogue Magazine bought and printed what Beaton himself later described as:

“…a slightly out-of-focus snapshot of him [Rylands] as Webster's Duchess of Malfi standing in the sub-aqueous light outside the men's lavatory of the ADC Theatre at Cambridge.”

His career began to take off, although he had to make do with designing book jackets and costumes for charity matinees and learning the professional craft of photography at the studio of Paul Tanqueray, until Vogue took him on regularly in 1927. Although never known as a highly skilled technical photographer, Beaton’s focus on staging a compelling model or scene and looking for the perfect shutter-release moment were what made his images so representative of the ‘Bright Young People’ of the twenties and thirties.

His career began to take off, although he had to make do with designing book jackets and costumes for charity matinees and learning the professional craft of photography at the studio of Paul Tanqueray, until Vogue took him on regularly in 1927. Although never known as a highly skilled technical photographer, Beaton’s focus on staging a compelling model or scene and looking for the perfect shutter-release moment were what made his images so representative of the ‘Bright Young People’ of the twenties and thirties.

Over the course of Beaton’s career he employed both large format cameras and smaller Rolleiflex cameras and often photographed the Royal Family for official publication. However, in stark contrast to the style and sophistication of his life within a glamorous circle of friends, colleagues and illustrious sitters, during the Second World War Beaton was initially posted to the Ministry of Information and given the task of recording images from the home front. During this assignment he captured one of the most enduring images of British suffering during the war - that of three-year-old Blitz victim Eileen Dunne (right) recovering in hospital, clutching her beloved teddy bear. When the image was published, America had not yet officially joined the war but, splashed across the press in the US, Beaton’s image (although, of course, not single-handedly) undoubtedly helped to persuade the American public to put pressure on their Government to help Britain at this dark time. This iconic image was entitled ‘The Age of Innocence’ and features in perhaps Beaton’s most sensitive documentary archive, ‘Air of Glory’ - a collection of photographs captioned by Rosamond Lehmann that touchingly reveal the indomitable spirit of those men, women and children fighting both abroad and, just as importantly, on the home front.

In his foreword to ‘Air of Glory’, Beaton tells us that:

“My camera has provided me with magic passes on to the sea and into the air.”

First published in 1941 and issued by the Ministry of Information, ‘Air of Glory’ aimed to document the ‘minutiae of the everyday’ during war time, sacrificing the panorama for individual detail. Beaton himself expresses this strive again, very clearly, in his foreword - seeming to me to have more poignancy to the modern day reader, perhaps even than it had at the time of printing:

“Today the constellations of barrage balloons, the arabesque of barbed wire, the paper lattice-work on the windows, the mushroom canteens, camouflaged pill-boxes, groundsel sprouting sandbags and marrow-planted ‘Andersons’ are to us on this fortress a sight too usual to be remarked. Tomorrow it may be interesting to look back upon these forgotten phenomena, now so intrinsic a part of this scene set in the most troubled time of civilization.”

As a visual account of life only two years into the Second World War, these truly are some of the most intimate portraits of a relatively recent history that so easily could have been lost due to, as Beaton himself terms it, “Goring’s repeated effort to frustrate my determination!”:

“His last attempt was made when the photographs were finished and assembled into various groups for the final sorting. A nearby bomb hurled the pictures like confetti, with most of the room that contained them, into a whirlwind of glass and cement rubble!”

Fortunately, the photographs only sustained superficial injuries of small scratches and cuts that are clearly visible in a few of the images adding, for the reader, a further dimension of the true reality of going about day-to-day life in a country at war.

Beaton survived the war and went on to tackle the Broadway stage, designing sets, costumes, and lighting for a 1946 revival of Lady Windermere's Fan, in which he also acted. He also designed the sets and costumes for a production of Puccini’s last opera Turandot, first used at the Metropolitan Opera in New York and then at Covent Garden and, bizarrely, the academic dress of the University of East Anglia! Beaton’s most high profile achievement was the previously mentioned costume design for Lerner and Loewe’s My Fair Lady (1956), which led to two Lerner and Loewe film musicals, Gigi (1958) and My Fair Lady(1964), both of which earned Beaton the Academy Award for Costume Design. In 1972 he was knighted but later that decade suffered a stroke and failing health until his death in January 1980, aged 76.

Cecil Beaton was also a well-known diarist. In his lifetime six volumes of his diaries were published, spanning the years 1922–1974. Recently a number of these diaries have been published that differ immensely in places to Beaton's original publications. Fearing law suits, it would have been imprudent for Beaton to have included some of his more frank and incisive observations in the first collections!

Contributed by Jane

(Published on 3rd Dec 2014 )