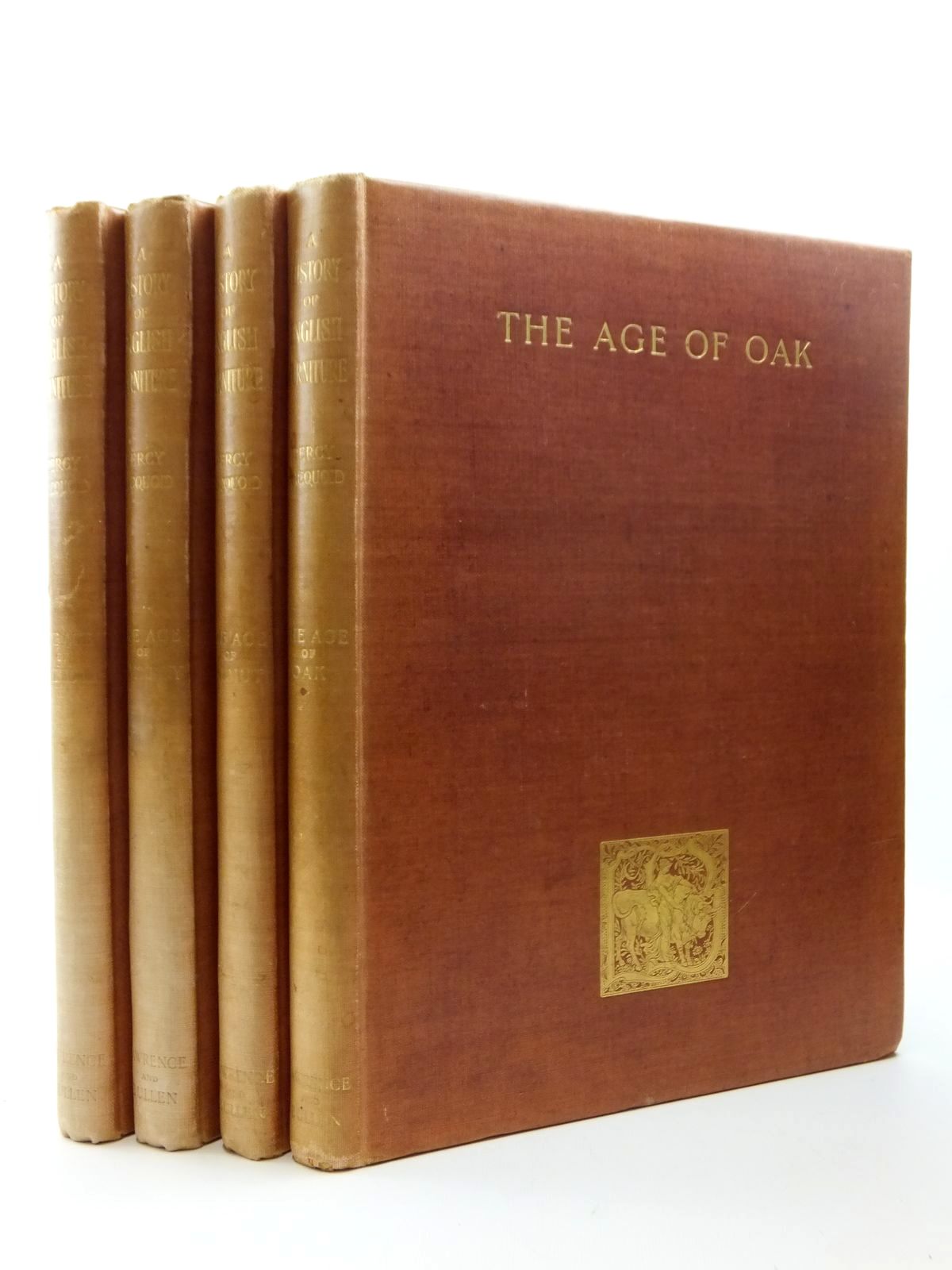

The History of English Furniture By Percy Macquoid

History – I hated the subject when I was at school – all those kings and queens and dates! Now I look around our history room in Stella & Rose’s books and there are so many fascinating titles. I wish history had been a more interesting subject when I was young, perhaps I would have paid more attention!

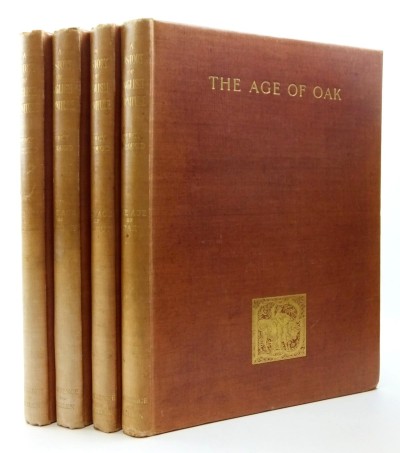

This four-volume set caught my eye – the history of furniture. Knowing nothing about the subject of furniture I thought it was worth a look. I had also never heard of the author so did a bit of research. I discovered that Macquoid, born in 1852, was a British theatrical designer and a collector and connoisseur of English furniture. In fact, this set of books was the first major survey of the subject and has been reprinted and still of use today.

Although the series deals specifically with the history, development and evolution of English furniture, the sources of inspiration and design can be traced to foreign origin, some examples of which are included.

The first volume in the series is “The Age of Oak”. This comprises furniture dating from 1500-1660 that can be attributed to the Renaissance and its evolution from the Gothic. It’s interesting that design in architecture and furniture in the Middle Ages was wholly due to the influence of the church. The author notes that early furniture was severe in character with a practical necessity for its solidity, as “a man armed cap-à-pie [head to foot] must have required a very heavily constructed seat”!

He continues “All very early English furniture that has come down to us is of oak. Deal and chestnut were rare, valuable woods in those days; what was made of beech and elm has perished and walnut was not grown for its wood till about 1500. The carting about of furniture over rough roads, when a great personage moved from one of his castles to another, must have demanded great strength in both material and construction”, therefore oak was given preference for its unquestionable durability.

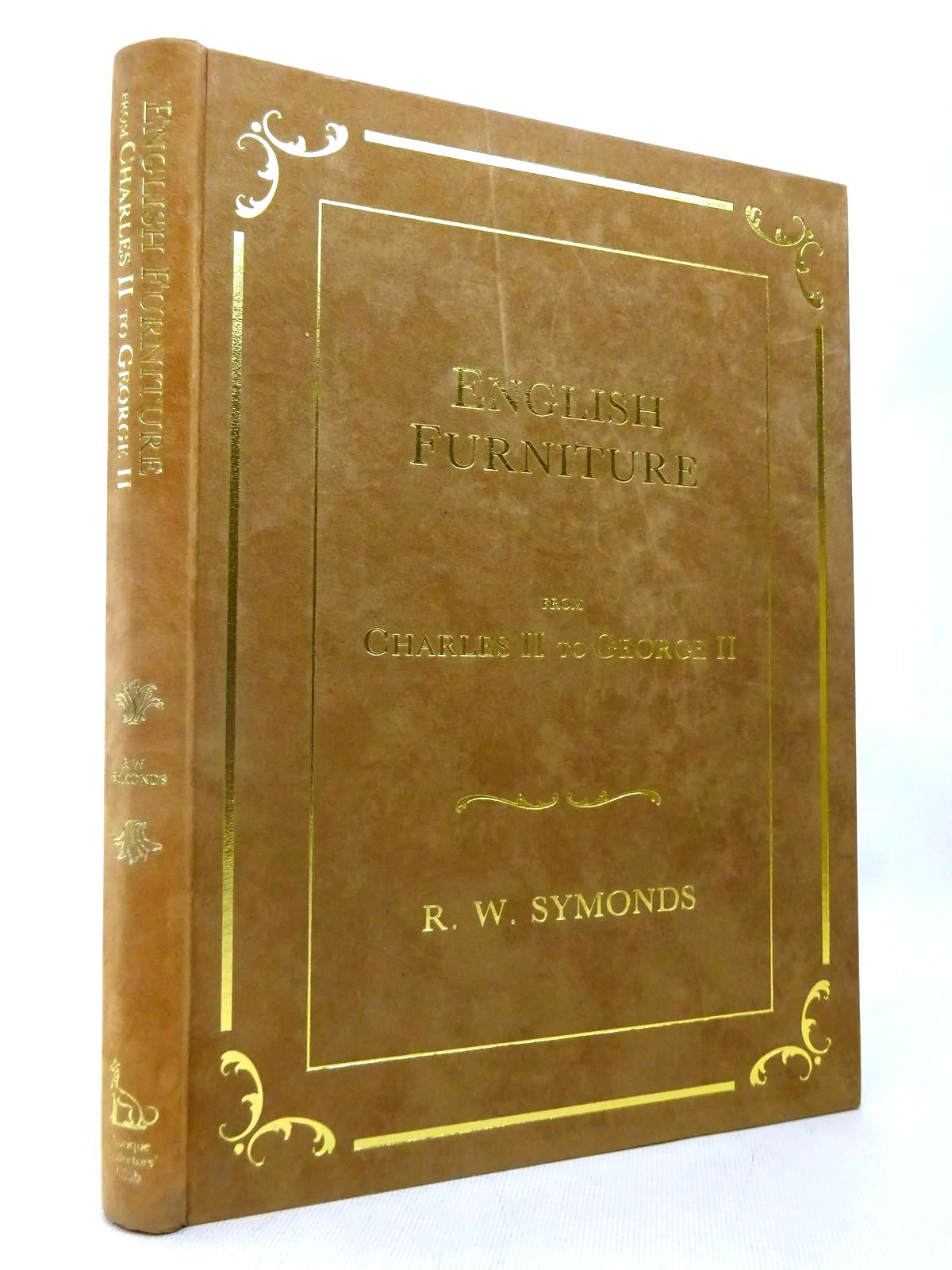

The second volume in the series is “The Age of Walnut”. On the third of September 1659 the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell died and “with him died the simple taste, that, owing to the dearth of imagination, had gradually drifted into the commonplace”. The Restoration of the Monarchy and the return of Charles II to the throne created a change of fashion in strong contrast to the existing conditions of social England. Influenced by France and Flanders and Italian artists, this period saw the introduction of rich furnishings, exaggerated mouldings, twists and curves.

Walnut had been adopted as a light wood to carry silks and satins, and a vast number of these trees had been planted during the reign of Elizabeth I. By the middle of the 17th century their timber had reached maturity. As well as the new designs in chairs, this period saw flamboyant upholstered bedsteads hung with embroidered drapes, decorated with fringes and tassels and the widespread use of marquetery for the ornamentation of small tables, clocks and other forms of furniture. Quite a contrast to the austere oak furniture of the Renaissance period.

Next we have “The Age of Mahogany”. The author writes “The first twenty-five years of the 18th century represent an almost stationary period in our artistic history.” Horace Walpole, writing of this time, was scathing in his remarks: “We are now arrived at the period in which the arts were sunk to the lowest ebb in Britain. The new monarch [George I of Hanover, Germany] was devoid of taste, and not likely at an advanced age to encourage the embellishment of a country to which he had little partiality”.

Mahogany began to be used in furniture construction between 1710 and 1715. Prior to this it had been used as a veneer or in small portions for decoration but by the year 1720 it was certainly being used for chairs, tables and settees. Being more expensive than walnut it was rapidly adopted by those wishing to be fashionable. It had properties of lightness unknown in oak, durability and strength deficient in walnut and the warmth of colour was also a novelty. Mahogany was imported in vast quantities initially from the Caribbean islands of San Domingo (Hispaniola) and Cuba and later from Honduras.

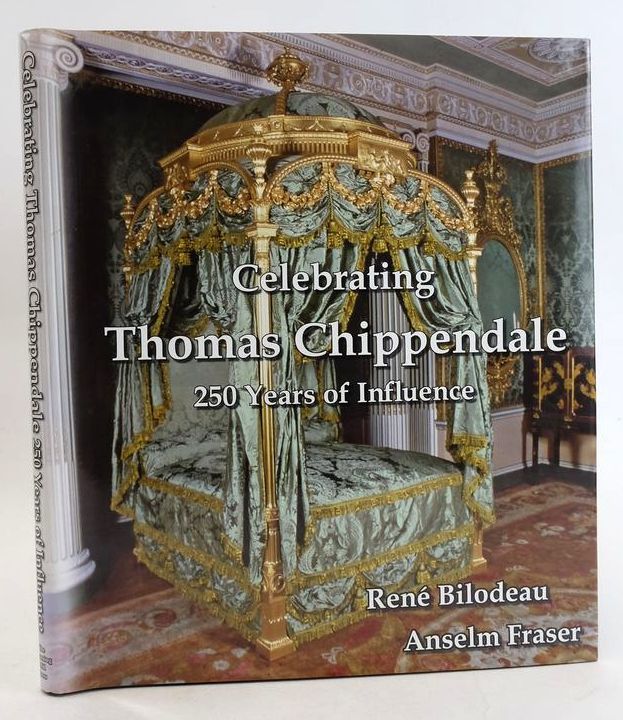

The author notes that “this wood was first used at a plain period of fashion in furniture but towards 1730 its decoration began and was hurried onwards in every conceivable variation by the various cabinet-makers, of whom Chippendale was perhaps the most consistent.”

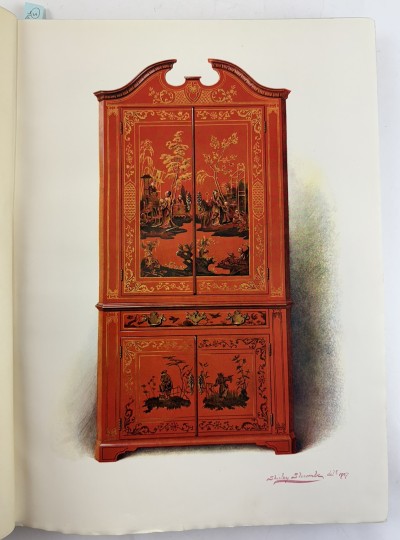

Last, but not least we have “The Age of Satinwood”. A considerable portion of the first chapter of this volume is devoted to the description of the art of lacquering, the differences between English, Dutch and Oriental lacquer and the “various eccentricities of the many Chinese crazes which have left a lasting mark on our furniture by introducing Chinese-Chippendale and English lacquer.’

The author’s description of satin-wood tells us that it is ‘cut from the tree Chloroxylon Swietenia. The best comes from Central and South India, is short and broad in the figure, and with age attains a brilliant warm yellow. It is extremely hard and gives out a curious aromatic scent when scraped.”

I was pleasantly surprised at how eminently readable these four volumes are. Not dry and dusty as my history lessons were but full of interesting facts and names I recognised even though my knowledge of antique furniture is scant! Full of black-and-white photographs of pieces of furniture along with beautiful colour plates, this is a mine of information for the lay person and collector alike.

I will let the author have the last word:

“With the close of the 18th century, originality and real beauty in English furniture ceased. Technically the work remained excellent, but as imagination and enthusiasm gradually disappeared, beautiful invention in domestic objects decayed and died; architecture, the parent of furniture, after the death of George III in 1820, became for the first time in England utterly ugly and uninteresting; textiles, plate, jewellery, as well as the necessary accompaniments of everyday life, were but imitations of former periods, and invention was concentrated on science, finance, and commercial enterprise in manufacture, little interest being taken in individual craftmanship.”

I wonder what Percy Macquoid would have said about flat packed furniture from Ikea!!

Contributed by Chris

(Published on 15th Aug 2025)