A NARRATIVE OF THE BUILDING AND A DESCRIPTION OF CONSTRUCTION OF THE EDYSTONE LIGHTHOUSE WITH STONE By John Smeaton

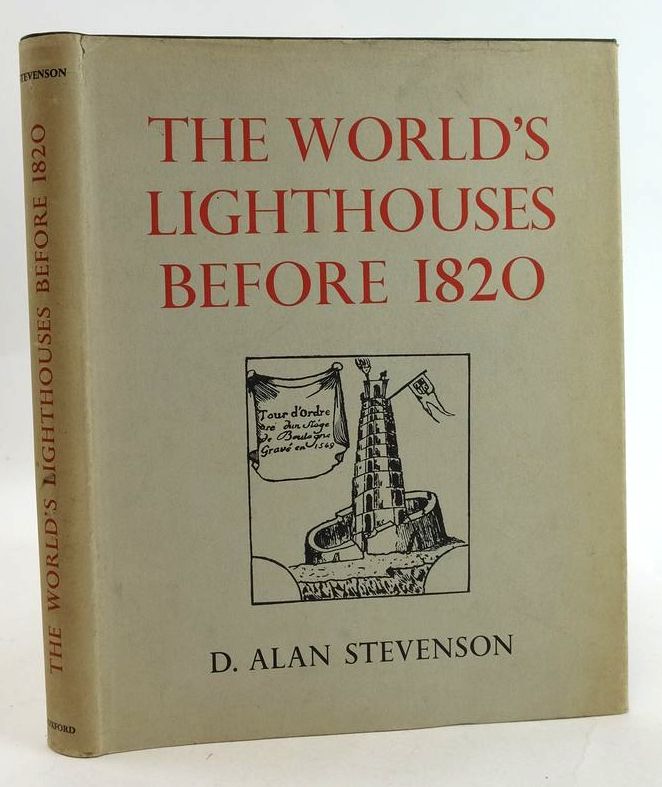

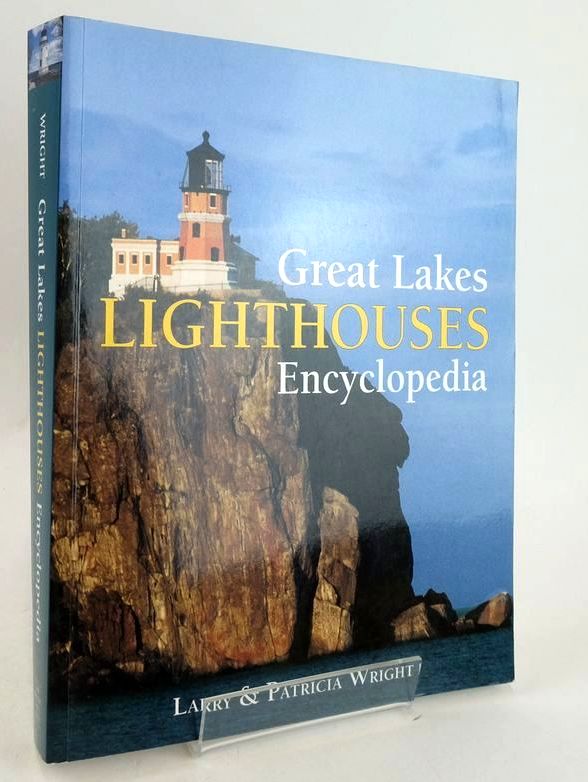

The treacherous Eddystone Rocks are situated 14 km off Rame Head in the South West of England and have always presented a terrifying hazard to shipping entering and leaving the major harbour of Plymouth in Devon. There have been four lighthouses built on the Eddystone, the first in 1698 and the current one in 1882; but it is John Smeaton's design and the innovative construction techniques that he used to build the third lighthouse that form the basis for all modern “rock” lighthouses.

The treacherous Eddystone Rocks are situated 14 km off Rame Head in the South West of England and have always presented a terrifying hazard to shipping entering and leaving the major harbour of Plymouth in Devon. There have been four lighthouses built on the Eddystone, the first in 1698 and the current one in 1882; but it is John Smeaton's design and the innovative construction techniques that he used to build the third lighthouse that form the basis for all modern “rock” lighthouses.

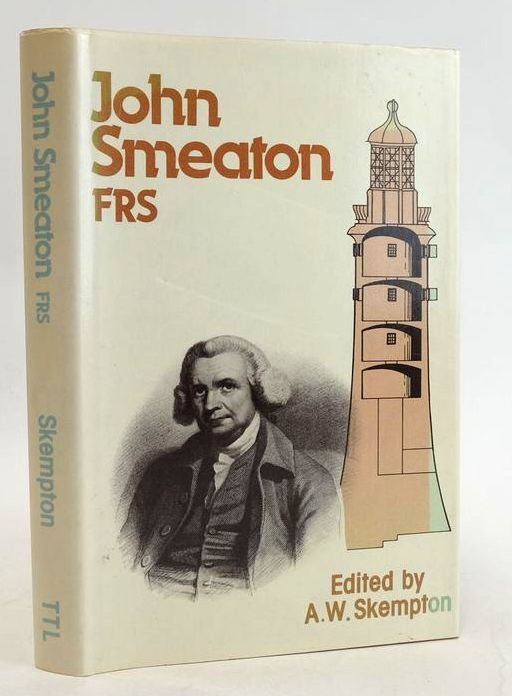

John Smeaton (1724-1792) was a gifted civil engineer who designed bridges, canals and harbours as well as lighthouses. In order to build the Eddystone lighthouse (note Smeaton in his book refers to the Edystone) he pioneered the use of Hydraulic Lime, a mortar that will set under water. He also developed a technique to secure the granite blocks using dovetail joints and marble dowels. Indeed so strong were his construction techniques that when the Victorian engineers came to remove his tower they were forced to leave the base which still stands to this day!

John Smeaton (1724-1792) was a gifted civil engineer who designed bridges, canals and harbours as well as lighthouses. In order to build the Eddystone lighthouse (note Smeaton in his book refers to the Edystone) he pioneered the use of Hydraulic Lime, a mortar that will set under water. He also developed a technique to secure the granite blocks using dovetail joints and marble dowels. Indeed so strong were his construction techniques that when the Victorian engineers came to remove his tower they were forced to leave the base which still stands to this day!

Right: Plan and Perspective elevation of the Edystone Rock view from the west.

There was no fault with Smeaton's lighthouse but the rock on which he had built was being undermined by the sea. Smeaton himself had noticed this possibility and had offered to secure the undercut rock for £250! Smeaton's tower still stands on Plymouth Hoe looking proudly out across Plymouth Sound to where it once stood on the Eddystone.

“I have printed but a small edition in point of number” - Smeaton's own words in the introduction to this scarce work. Smeaton, in the early chapters of this book, looks at the ancient lighthouse at Pharos as well as the two lighthouses that preceded his on the Eddystone. The first by Winstanley which disappeared in a great storm with its builder who was inside at the time and that of Rudyerd that burnt

down.

South Elevation of Winstanley lighthouse>

Smeaton, on being asked to design the lighthouse had no hesitation in deciding that it must be of stone and he describes in detail how his lighthouse shape was inspired by the oak tree and one of the plates illustrates his inspiration.

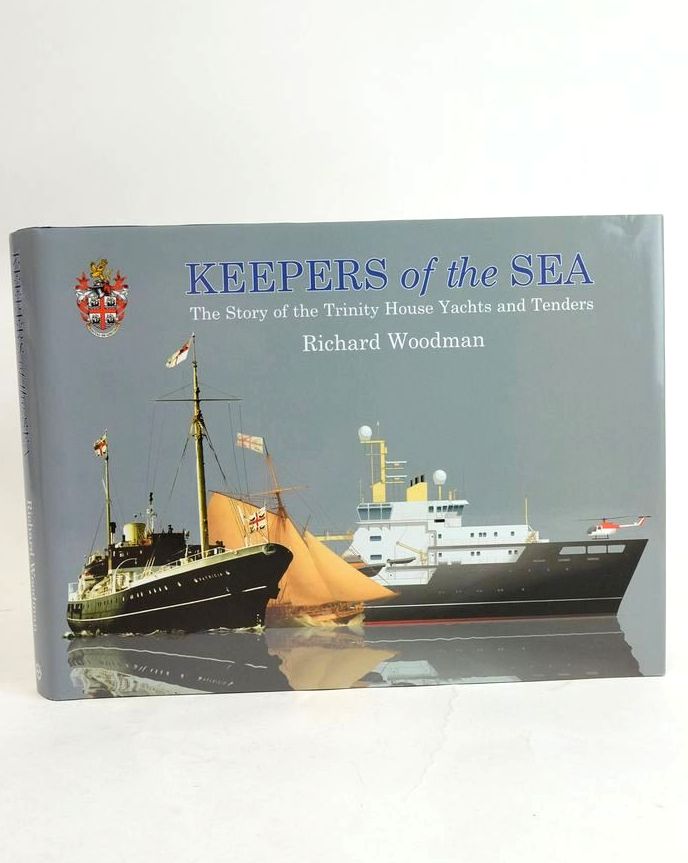

From a distance of 200 years we can easily forget the logistical challenges of moving men and materials in rough seas to and from the Eddystone and again Smeaton's book describes in detail the sailing arrangements and how, dependent on the vagaries of wind and tide, he would end up in Fowey rather than Plymouth. Indeed on one occasion Smeaton and the crew were in very grave danger and were swept away by a storm way to the South West of Cornwall to Land's End and were even considering that they may have to let the storm take them to France, such was their plight.

Smeaton may have led but the work was carried out in awful conditions on the rock by mainly anonymous workers and Smeaton provides us with what is, in many respects, a recognisably modern “employment contract” for the workers and their rates of pay with perhaps some contemporary exceptions: “All persons to victual themselves but a bowl of Punch to be allowed each company on their return on shore”. The rates of pay varied considerably depending on whether the person was on shore or on the rock. A mason was paid 2s 6d per day certain at sea with a premium of 9d per hour, but on land only 20d per day (s = shillings, d = pence).

Even great engineers can be thwarted by the irritating errors of those in their employ as when Smeaton had a wasted journey to the rock...the carpenter had neglected to bring off a paper (sic) of nails that he was expressly ordered to bring and REMINDED of... (Smeaton's emphasis!) Smeaton had ongoing labour problems - “I have always found it more difficult to manage the workmen employed than to control the elements”. French privateers were also a concern as they were seen in the area – remember Britain and France were at war at that time.

Since the lighthouse was to be built of stone Smeaton visited several quarries in Cornwall and Dorset (Portland) to select the stone and provides us with detailed descriptions of the quarries and their methods of working. He devotes a great deal of space to providing exhaustive information on his “Experiments on Water Cements” and it's astonishing at how widely throughout the UK he sourced various limestones for his experiments.

The morning after a Storm - part of the title page>

The Portland stone was brought by ship from Portland and Smeaton is often fretting on when the next ship would come and amongst his many troubles one shipment was delayed because the Royal Navy press-ganged the crews of boats carrying the stone! In the early stages of construction when the sea was still breaking over the lower courses many huge stones were washed away demonstrating the enormous power of the ocean. Smeaton himself was washed off the rock into sea but treats the situation very casually - during the fall he had dislocated his thumb and describes how he set it straight himself on a flat rock!! He also had to contend with the fishermen from Polperro stealing the cork buoys that were essential for mooring the boats transporting the stones.

Despite all the setbacks the light was lit on the 16th October 1759 and Smeaton over the next 30 years made regular inspection visits. Smeaton concludes this mighty work with a description of his building the lighthouse at Spurn Point in Yorkshire. 'Mighty' is an apt description as this book is huge in size and, though packed with the the technical detail of the construction materials and techniques, I personally enjoy the “asides” - being swept away, men being press ganged, the French privateers and especially his remarks about “the men”. A rare book and a rare insight into the eighteenth century.

Contributed by Cliff

(Published on 10th Dec 2014 )