William Brown

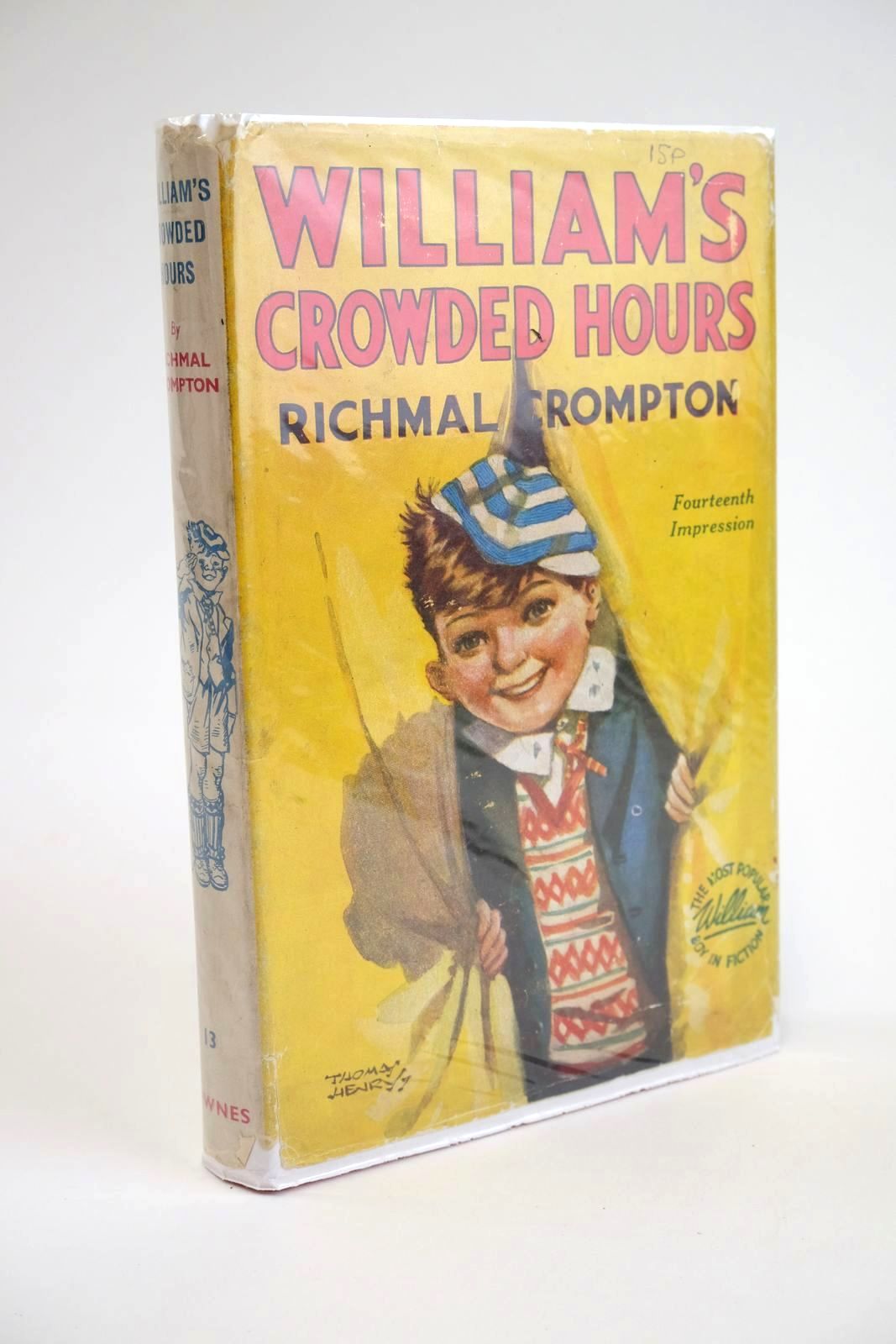

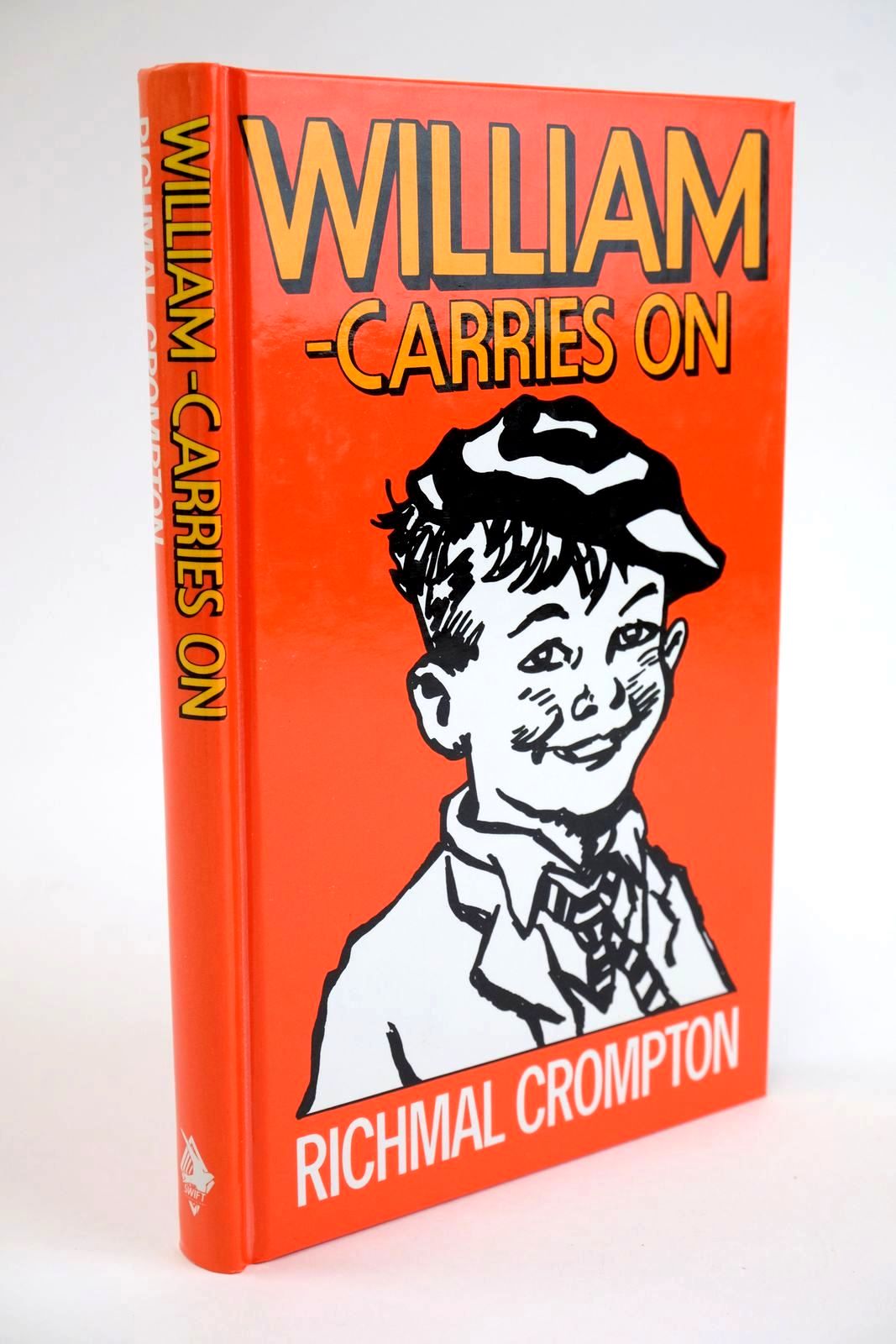

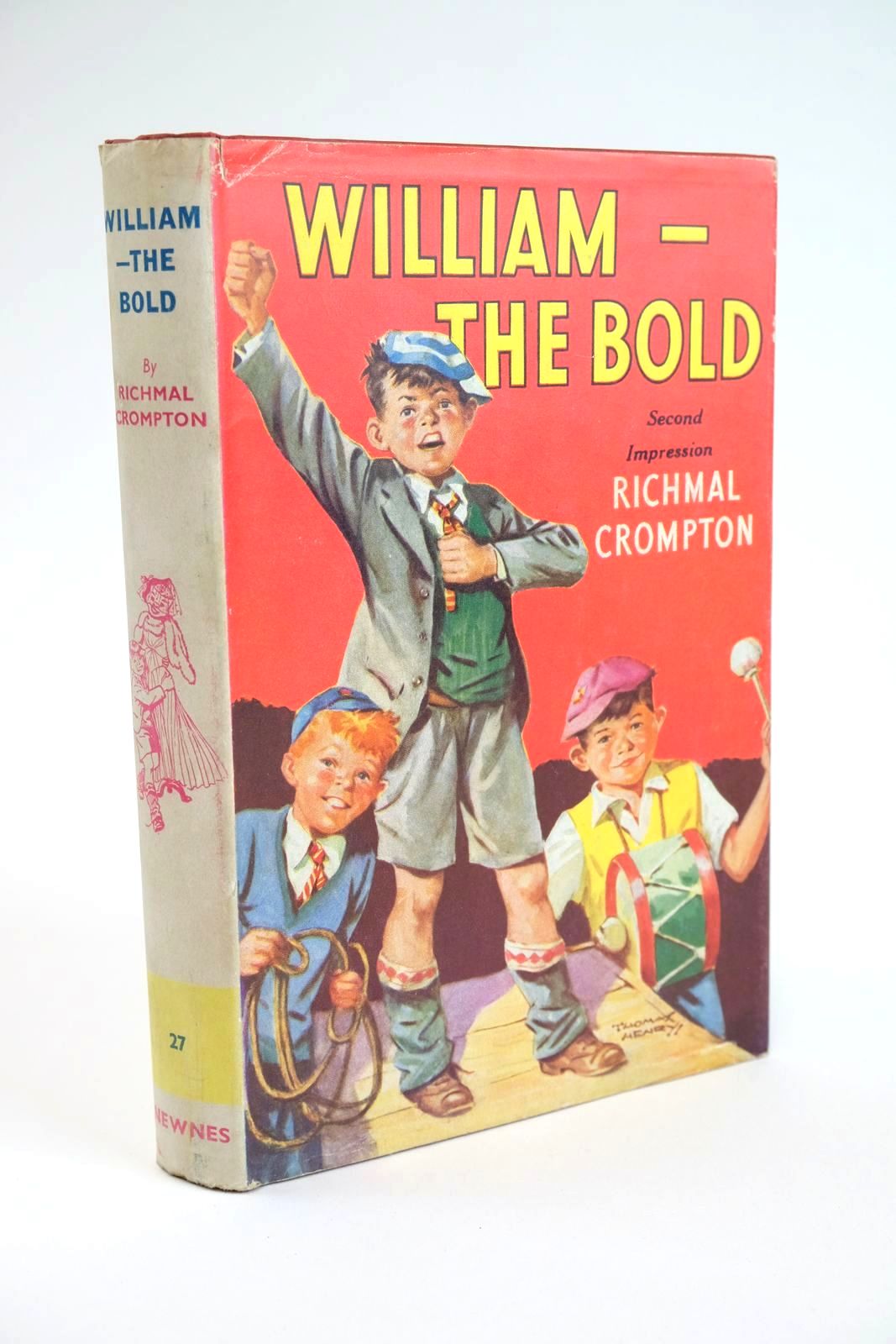

View current stock of William books

View current stock of William books

He is one of the strongest and most vividly drawn characters in all fiction.

She was a private person not overly well known.

He stands comparison with Mr. Micawber, Long John Silver, Falstaff, Sherlock Holmes and Tom Sawyer – in fact, he is more rounded a character than any of them.

She stands comparison with Maupassant, Somerset Maugham, O’ Henry and Mark Twain --- and, although her range may not be as broad, she is funnier than any of them.

He is William Brown, the ultimate boy.

She is Richmal Crompton, his inspired genius of a creator who, even today, is sometimes taken by even her fans as a man because of her unusual first name.

Even describing him as the ultimate boy does not do justice to the scowling, befreckled, crumpled suited, socks down, hands-in-pockets, hair awry, energy filled entity that is William; a being that stormed through 38 books and innumerable escapades (at least 345 short stories plus cartoons plus television and radio adaptations).

William first saw the light of print in 1919; twenty-nine years after his creator (so different from her brain child) had been born in the outskirts of Bury. Richmal Crompton Lamburn was a daughter of a clergyman and enjoyed a relatively comfortable up bringing. ‘Ray’ as she became known was always to remain close to her elder (by seventeen months) sister Mary Gwendolen. Completing the family came John, two and an half years after Richmal, the ever-beloved young brother.

Richmal’s father had chosen to teach in preference to parish work. He believed passionately in the value of education and his children benefited from his teaching at home. Well, two of them did. Richmal and Gwen absorbed all he threw at them; happily they dived into the great well of the classical world and drank deeply.

Richmal’s father had chosen to teach in preference to parish work. He believed passionately in the value of education and his children benefited from his teaching at home. Well, two of them did. Richmal and Gwen absorbed all he threw at them; happily they dived into the great well of the classical world and drank deeply.

John (Jack) was another matter. Jack was to be the prototype for the world’s most rumbustious eleven year old. Like so many of the youngest in a family Jack walked to his own drumbeat. He was not greatly interested in schoolwork and parental disapproval scarcely moved him. It had probably never struck Richmal or her sister that such an attitude could be adopted. Richmal and Gwen lived and luxuriated in the ancient worlds of Rome andGreece --- but Jack was a boy and the open fields and real adventure, as opposed to vicarious, beckoned. Surely many of William’s interests were Jack’s; teaching insects tricks, studying frogs, climbing trees, playing Red Indians in the undergrowth, splashing into ditches, pinching apples, being chased by farmers...

But if Jack was the original inspiration (later Richmal would learn from her nephew and then her great nephew) it was the deep, perceptive and sensitive intelligence of Richmal herself that understood and developed what she observed and, above all, that could project her understanding into another being so dissimilar.

But if Jack was the original inspiration (later Richmal would learn from her nephew and then her great nephew) it was the deep, perceptive and sensitive intelligence of Richmal herself that understood and developed what she observed and, above all, that could project her understanding into another being so dissimilar.

Yet she was something of a tomboy. She loved the games at St. Elphin's School for the Daughters of the Clergy when she joined in 1901. Cricket, tennis and hockey became her passion. She had the advantage of Gwen going before her and life there, back in those Edwardian days of innocence, suited her ideally. She was also keen on the amateur theatricals of the school and these, perhaps, inspired her first attempts at writing; she produced playlets and poetry for all occasions.

She had caught the creative bug early on and for that there is no known cure. Richmal graduated in the classics from Royal Holloway College (where she had added to her sports by taking up rowing) in the fateful and fatal year of 1914. Her report particularly mentioned her ‘mastery of language.’ The offspring of her mind however scorned such learning:

“ – if they wanter talk to me they can learn English. English’s easy to talk. It’s silly having other langwidges. I don’t see why other countries shun’t learn English ‘stead of us learnin’ other langwidges with no sense in ‘em. English’s sense.”

Jack had been lucky. Craving excitement he had joined the Rhodesian Mounted Police in 1913 and, although desperate to join the forces and fight in France when the War broke out, he was tied in Africa for the duration. Later, he was to use this experience to write himself, producing several adventure novels of note (‘Trooper Fault’ is probably the most well known) and (writing this time under the name John Crompton as opposed to John Lambourne) also to produce a number of naturalist books of which one, ‘The Hunting Wasp,’ was to become a standard reference work in its field (and is still available).

Jack had been lucky. Craving excitement he had joined the Rhodesian Mounted Police in 1913 and, although desperate to join the forces and fight in France when the War broke out, he was tied in Africa for the duration. Later, he was to use this experience to write himself, producing several adventure novels of note (‘Trooper Fault’ is probably the most well known) and (writing this time under the name John Crompton as opposed to John Lambourne) also to produce a number of naturalist books of which one, ‘The Hunting Wasp,’ was to become a standard reference work in its field (and is still available).

Richmal returned to St. Elphin’s as classics mistress in the autumn of 1914 (Gwen had started a job in London in the business field). She not only enjoyed teaching but also, by all accounts, was an immensely successful and popular teacher well able to stimulate and hold the interest of her pupil. She left, however, in 1917 to follow her recently widowed mother to the city. Gwen had now married and there was also the attraction of a young nephew on the London scene.

She set up home with her mother some three miles from her new school (Bromley High School – a girls’ public day school) and happily cycled in every day. But she continued to write. These were the great days for short stories of all types. Magazines of all descriptions flourished without the competition of radio and only slight competition from the embryonic cinema. Richmal’s first story appeared in Girl’s Own Paper in 1918. As with the later William tales (whom it foreshadows being about a small boy called Thomas ---- but with no where near the same impact) it was well constructed with a clear beginning, middle and end and even a summing-up or twist at the end. Although known as Ray Lambourne at school, Richmal used her real first name along with her middle name because the school did not permit its employees to have other jobs and she was afraid that being a writer would count as such. In fact, when the school discovered they had the writer of the William series on their hands, far from decrying her, they were delighted and (naturally) proud to have such a person on their staff.

She set up home with her mother some three miles from her new school (Bromley High School – a girls’ public day school) and happily cycled in every day. But she continued to write. These were the great days for short stories of all types. Magazines of all descriptions flourished without the competition of radio and only slight competition from the embryonic cinema. Richmal’s first story appeared in Girl’s Own Paper in 1918. As with the later William tales (whom it foreshadows being about a small boy called Thomas ---- but with no where near the same impact) it was well constructed with a clear beginning, middle and end and even a summing-up or twist at the end. Although known as Ray Lambourne at school, Richmal used her real first name along with her middle name because the school did not permit its employees to have other jobs and she was afraid that being a writer would count as such. In fact, when the school discovered they had the writer of the William series on their hands, far from decrying her, they were delighted and (naturally) proud to have such a person on their staff.

William first appeared in a ladies’ magazine in February of 1919. Surprisingly, he jumped in fully developed. The William of ‘Rice Mould’ (the first story) is exactly the same character that appeared in ‘William the Lawless’ (the last book) of 1970 (a posthumous book as Richmal died early in 1969).

William first appeared in a ladies’ magazine in February of 1919. Surprisingly, he jumped in fully developed. The William of ‘Rice Mould’ (the first story) is exactly the same character that appeared in ‘William the Lawless’ (the last book) of 1970 (a posthumous book as Richmal died early in 1969).

There are other differences however. The early William stories were written with an adult audience in mind and both the English used, the references --- ‘said William with the air of a Rothschild’ – and the mild satire would not necessarily be appreciated or understood by most children. In fact Crompton is such a good writer that she performs the trick of letting her reader see the situation from both points of view.

The large woman bears down on him with her photograph album. “You can look at the album while I’m getting ready,” she says and William realises he is trapped – ‘trapped in a huge and horrible drawing-room by a huge and horrible woman.’

We can see it from William’s point of view both as children and as adults yet children would have no sense of the difficulty adults sometimes experience in entertaining them – particularly those adults who have forgotten their own childhood --- so we can have a sympathy with the large woman.

The series was to gently segue into one for children (albeit of all ages from eight to eighty). Later stories were to be more farcical and the adults in them were to act and react more in the manner that children would want them to (hysterics and swooning are frequent) rather than as they really would.

The series was to gently segue into one for children (albeit of all ages from eight to eighty). Later stories were to be more farcical and the adults in them were to act and react more in the manner that children would want them to (hysterics and swooning are frequent) rather than as they really would.

As Richmal advanced in her writing career --- the first William book (with stories ludicrously out of order compared to the chronology of them in the magazine) appeared in 1922 --- her publishers pressed her to devote herself to literature particularly as she was by then producing other fiction aimed entirely at adults. The decision was largely taken out of her hands. The gods do not like those whom they gift being sparing of their talents. In summer of 1923 she contracted the feared disease of poliomyelitis.

After the attack she was permanently paralysed in one leg.

After the attack she was permanently paralysed in one leg.

Courageously she continued to teach – struggling into school by cycling the almost four miles with her dead leg sticking out an odd angle. Eventually it was too much even for her. She did as her publisher wanted her to.

Of Richmal’s adult output ‘Family Roundabout,’ ‘Felicity Stands By’ and ‘Kathleen and I and, of course, Veronica’ are probably the best and deserve better recognition than they generally get. They provide an insight into the middle-class world of their day -- -and they are funny; but William has long eclipsed them. Richmal herself did think of ending with William early on and it was her then editor who suggested she continue with him even as a side character in some of her stories.

But once William was in, William was in --- how could such an individual as he ever play a minor role. Richmal simply could not stop making up tales about that enfant terrible. And he is far more complex than simply being a ‘naughty boy’ – indeed he is not such although it would be hard to convince the adults he tangles with of that. Behind his actions there is a logic (albeit cack-handed) and a well developed sense of honesty whether he is trying to achieve justice (because he also has a highly if eccentrically developed sense of justice), whether he is trying to help (wanted or not) or whether he is simply attempting to raise money to visit a circus. His world is the village world of England of the early years of the last century and through his eyes we can see that world and its characters and its manners, its standards and its habits. We can see it pulling together in wartime; we can view its crazes and its normal daily round. The types are well set; the General, the newly rich (from commerce) that are already nibbling at the long established landed gentry, the eccentrics and artists (almost the same) that seek refuge and inspiration in the village and from it, the local shopkeepers and the farmers (the last especial enemies of William).

But once William was in, William was in --- how could such an individual as he ever play a minor role. Richmal simply could not stop making up tales about that enfant terrible. And he is far more complex than simply being a ‘naughty boy’ – indeed he is not such although it would be hard to convince the adults he tangles with of that. Behind his actions there is a logic (albeit cack-handed) and a well developed sense of honesty whether he is trying to achieve justice (because he also has a highly if eccentrically developed sense of justice), whether he is trying to help (wanted or not) or whether he is simply attempting to raise money to visit a circus. His world is the village world of England of the early years of the last century and through his eyes we can see that world and its characters and its manners, its standards and its habits. We can see it pulling together in wartime; we can view its crazes and its normal daily round. The types are well set; the General, the newly rich (from commerce) that are already nibbling at the long established landed gentry, the eccentrics and artists (almost the same) that seek refuge and inspiration in the village and from it, the local shopkeepers and the farmers (the last especial enemies of William).

Much of the humour derives from the difference between William’s viewpoint and that of the grown-up world and, in a broader sense, the down-to-earth way children have of viewing the world and society. “Do you know who I am?’ says the great actor striking an attitude and William replies simply, ‘No, an’ I bet you don’t know who I am either.”

Much of the humour derives from the difference between William’s viewpoint and that of the grown-up world and, in a broader sense, the down-to-earth way children have of viewing the world and society. “Do you know who I am?’ says the great actor striking an attitude and William replies simply, ‘No, an’ I bet you don’t know who I am either.”

The adults that pervade William’s world are generally disapproving. Robert, William’s older brother, is the typical late teenage youth of the early and mid- Twentieth Century. His age actually varies (not the only minor mistake Richmal makes through the series). He ranges from 17 through 18 to 19 (Ethel is always given as 19) whilst William stays, defiantly, on 11 and almost three-quarters. Robert, to William, is part of the adult world and yet, when the series is read as an adult, the insecurities and sudden passions of that age pick Robert out as clearly a ‘raw’ youth.

Ethel also plays a sophisticate to her many admirers (she must have had more admirers than any other girl in the world). That’s not surprising when her effect is so keenly described; -

Ethel also plays a sophisticate to her many admirers (she must have had more admirers than any other girl in the world). That’s not surprising when her effect is so keenly described; -

Suddenly someone appeared in the doorway. To the young man it was as if a radiant goddess had stepped down from Olympus. The barn was full of heavenly light. He went purple to the roots of his ears.

To William it was as if a sister whom he considered elderly and disagreeable and entirely devoid of all personal charm had appeared.

Yet the elderly nineteen-year-old Ethel is still a girl who turns to her mother when she needs help --- particularly when William is concerned. Not that she ever receives the help she seeks in that quarter because Mrs. Brown, placid and patient, views William in a different light from everyone else. “She likes him,” exclaims an amazed Robert. Mrs. Brown is always prepared to believe in the best of her youngest son.

This is unlike his father who, when his host comments that he’d like to meet his son, answers: “I prefer people who haven’t met him. They can’t judge me by him.”

The character of Mr. Brown is complex. At one level he is almost an Edwardian father (remember Richmal penned the first William in 1918). He is stiff and formal and never shows any overt fondness for William. “There are moments, William,” Mr. Brown says at the end of William and the Smuggler after William has driven off a particularly boorish individual, “when I feel almost affectionate towards you.” Mr. Brown spends most of his home life relaxing in his chair reading his all-precious newspaper and never speaks to William accept to either chase him off or to drop witty sarcasms on his head – sarcasms that invariably bounce off that appendage.

The character of Mr. Brown is complex. At one level he is almost an Edwardian father (remember Richmal penned the first William in 1918). He is stiff and formal and never shows any overt fondness for William. “There are moments, William,” Mr. Brown says at the end of William and the Smuggler after William has driven off a particularly boorish individual, “when I feel almost affectionate towards you.” Mr. Brown spends most of his home life relaxing in his chair reading his all-precious newspaper and never speaks to William accept to either chase him off or to drop witty sarcasms on his head – sarcasms that invariably bounce off that appendage.

Yet Mr. Brown is often brought in as the chastiser of his reprobate offspring and, at times, one suspects he’s playing a part rather than carrying out what strict morality demanded. “It’s disgraceful,” Mr. Brown says after one particular incident where William has exhibited his sleeping and snoring aunt for the edification and delight of the neighbourhood children --- ‘Fat Wild Woman Torkin Natif Langwidge,’ states the notice by her bed ---- but as the aunt has now left the house in indignant outrage promising never to return something hard and round is slipped to William by his father. In a later tale something similar happens when Mr. Brown first strikes an attitude of stern disapproval towards William and then, when he learns that William’s actions have ensured Mrs Beverton will never be coming again, he changes tune, ‘Yes, yes, the boy obviously meant no harm. I can’t see what you’re all making this fuss about. Actually, when you come to think of it, he was trying to help. I can’t understand why you’re so hard on the child.”

The little imaginative “why you’re so hard on the child” ties Mr. Brown in with William. Mr. Brown may be something in the city and travel to London each day and be perfectly respectable and behave very properly but he is the father of William and William is his son --- and Jack peeks out from both.

The little imaginative “why you’re so hard on the child” ties Mr. Brown in with William. Mr. Brown may be something in the city and travel to London each day and be perfectly respectable and behave very properly but he is the father of William and William is his son --- and Jack peeks out from both.

The Outlaws, William’s gang, are all distinctly drawn individuals as well. There is Ginger (whose second name confusingly changes from Flowerdew to Merridew during the series – but never mind). Ginger is the second-in-command behind William and secretly admires his leader and tries to emulate him. Henry is the oldest of the Outlaws and tries to appear wiser and more knowing; Douglas is the perennial pessimist (as against William, the eternal optimist) and the one most inclined to hang back. He also enjoys a reputation amongst the Outlaws for having a way with words: -

Gnites of the Square tabel,

Rongs Wrighted 6d and 1/-

Pleese gnock

Douglas writes this on a notice board when the Outlaws set out to emulate King Arthur. William points Douglas out with pride to the young man who, intrigued by the notice, enters the old barn where the gnites sit waiting to wright rongs.

Douglas writes this on a notice board when the Outlaws set out to emulate King Arthur. William points Douglas out with pride to the young man who, intrigued by the notice, enters the old barn where the gnites sit waiting to wright rongs.

“I should like to shake hands with you,” the young man says respectfully, duly impressed by Douglas’s use of English. Douglas, much gratified by this, shakes willingly.

This band is the childhood elite of the neighbourhood. Naturally they have enemies – apart from the grown-up world – and these take the shape of sneaky Hubert Lane and his effete followers who can never get the better of William except by nasty skulduggery and sly cunning (and even that fails in the end).

William, of course, always has trouble with those inferior creatures; girls. His dealings with them are never simple. Joan, his next-door neighbour, is the best of them because she is an open admirer of him, “You do such ‘citing things,” the placid Joan tells him.

“William,” whispers Joan from her window at the end of a day that saw both of them in trouble, ‘you don’t like her better than me, do you?” She refers to another girl that had been involved in the adventure.

William considered. “No, I don’t,” he said at last.

A soft sigh of relief came through the darkness. “I’m so glad! Go’-night, William.”

Go’-night,” said William sleepily, drawing down his window as he spoke.

Tristram and Issolde: Heathcliffe and Catherine: Romeo and Juliet: William and Joan.

Violet Elizabeth Bott was another matter for William. Like William she is an extremely strong character (perhaps the most horrid child in all literature) and proves a devastating presence. Here is her first meeting with William: -

Violet Elizabeth Bott was another matter for William. Like William she is an extremely strong character (perhaps the most horrid child in all literature) and proves a devastating presence. Here is her first meeting with William: -

"My nameth Violet Elizabeth.” He received this information in silence. “I’m thix.”

He made no comment. He examined the distant view with an abstracted frown.

“Now you muth play with me.”

William allowed his cold glance to rest upon her. “I don’t play little girl’s games,” he said scathingly. But Violet Elizabeth did not appear to be scathed.

“Don’ you know any little girlth?” she said pityingly. “I’ll teach you little girlth gameth,” she added pleasantly.

“I don’t want to,” said William, “I don’t like them. I don’t like little girls’ games. I don’t want to know ‘em.”

Violet Elizabeth gazed at him open mouthed.

“Don’t you like little girlth?” she said.

“Me?” said William with superior dignity. “Me? I don’t know anything about them. Don’t want to.”

“D-Don’t you like me?” quavered Violet Elizabeth in incredulous amazement. William looked at her. Her blue eyes slowly filled with tears, her lips quivered.

“I like you,” she said, “don’t you like me?” William stared at her in horror.“You – you do like me, don’t you?”

William was silent.

A large shining tear welled over and trickled down the small pink cheek. “You’re making me cry,” sobbed Violet Elizabeth. “You are. You’re making me cry, ‘cause you won’t thay you like me.”

“I- I do like you,” said William desperately. “Honest – I do. Don’t cry. I do like you. Honest!”

A smile broke through the tear stained face.

“I’m tho glad,” she said simply. “You like all little girlth, don’t you?” She smiled at him hopefully. “You do, don’t you.”

It was a nightmare to William. They were standing in full view of the drawing-room window. At any moment a grown-up might appear. He would be accused of brutality, of making little Violet Elizabeth cry. And, strangely enough, the sight of Violet Elizabeth with tear-filled eyes and trembling lips made him feel that he must have been brutal indeed. Beneath his horror he felt bewildered.

“Yes, I do,” he said hastily. “I do. Honest I do.”

She smiled again radiantly through her tears. “You with you wath a little girl, don’t you?”

“Er- yes. Honest I do,” said the unhappy William.

“Kith me,” she said raising her glowing face. William was broken.

Violet Elizabeth with her proud threat to “Thcream an’ thcream till she’s sick” haunts William in many an escapade. Disappointingly, the BBC, in a fit of misplaced political correctness, dropped Violet Elizabeth’s famous lithp in the last William series it ran. This displayed a complete misunderstanding of the character and her relationship with William. Richmal Crompton, handicapped herself, uses the slight drawback of a lisp not to make fun of Violet Elizabeth but to demonstrate how a positive response can be given by such a child to any taunting. Every time William attempts to mock her lisp, Violet Elizabeth reverses the tables and gets the better of our non-plussed hero. “Oh William” she laughs, “You are tho funny,” and William becomes vaguely uneasy that the laugh is on him.

Violet Elizabeth with her proud threat to “Thcream an’ thcream till she’s sick” haunts William in many an escapade. Disappointingly, the BBC, in a fit of misplaced political correctness, dropped Violet Elizabeth’s famous lithp in the last William series it ran. This displayed a complete misunderstanding of the character and her relationship with William. Richmal Crompton, handicapped herself, uses the slight drawback of a lisp not to make fun of Violet Elizabeth but to demonstrate how a positive response can be given by such a child to any taunting. Every time William attempts to mock her lisp, Violet Elizabeth reverses the tables and gets the better of our non-plussed hero. “Oh William” she laughs, “You are tho funny,” and William becomes vaguely uneasy that the laugh is on him.

On the whole though, the BBC productions have been excellent --although no definitive William has surfaced – none such ever could. Possibly the young Dennis Waterman came closest in the 1962 series. However Diana Dors proved her acting skills as the dreadful Mrs. Bott in the 1977 series --- a series significant for the emergence of the highly capable Bonnie Langford in the role of Violet Elizabeth.

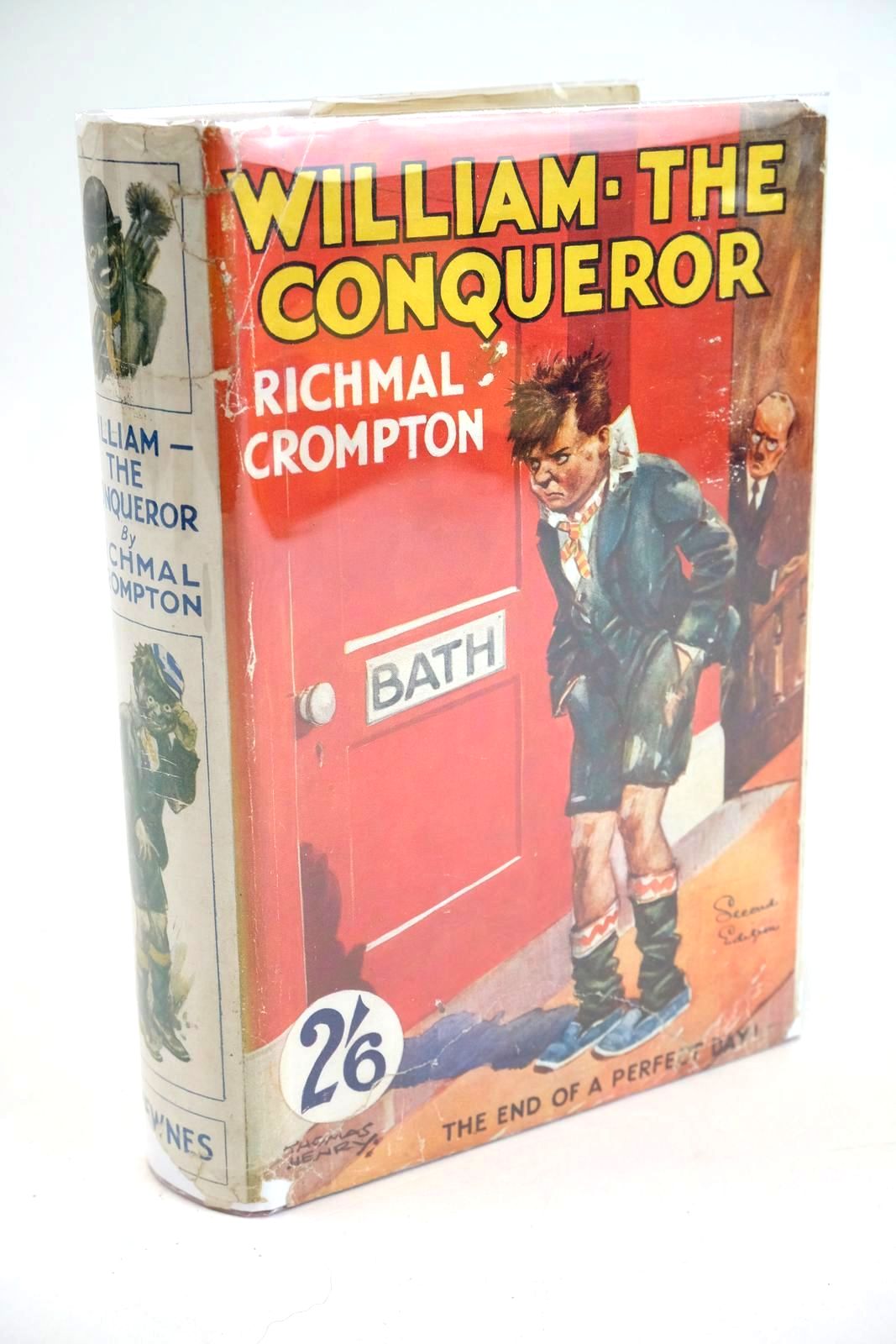

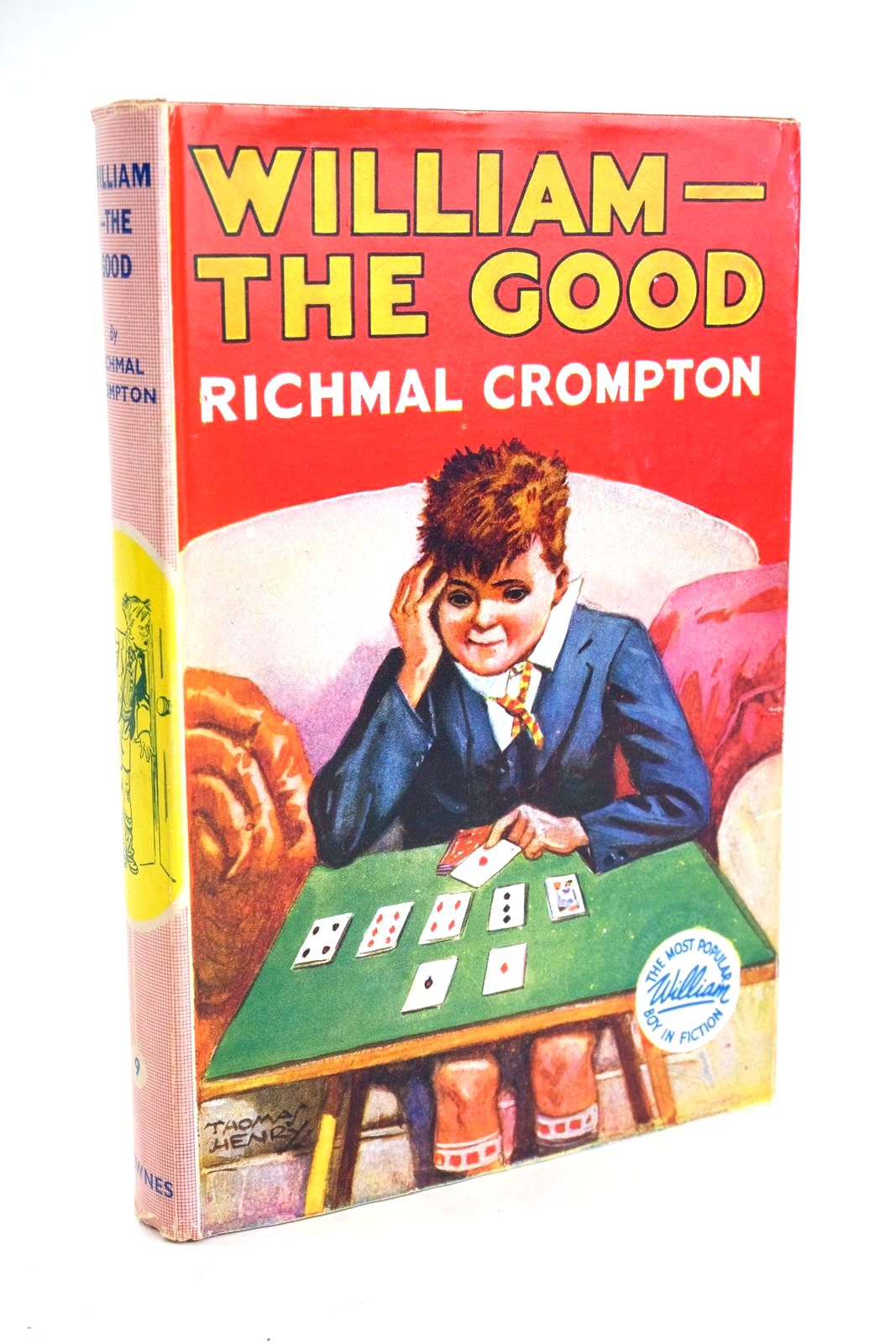

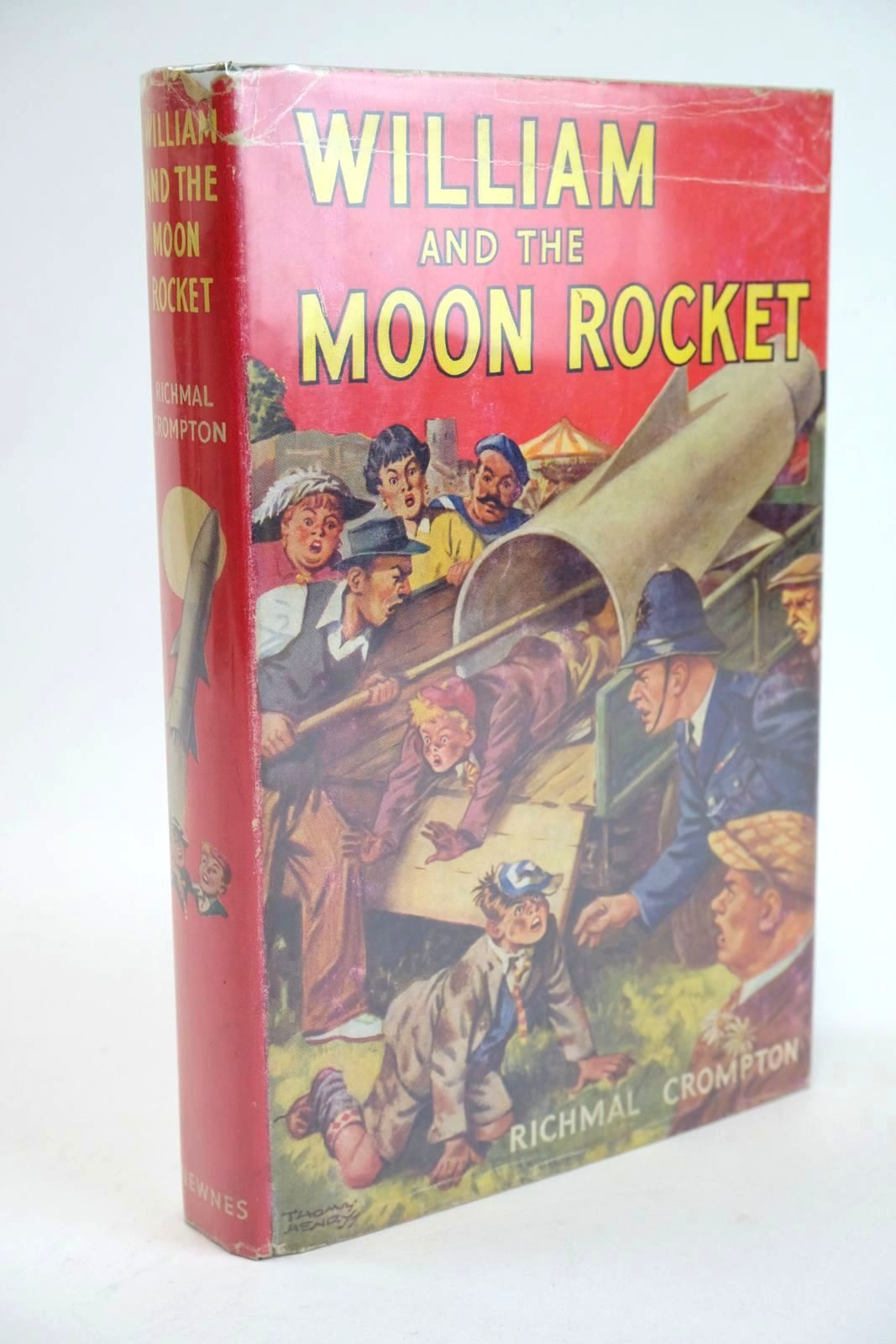

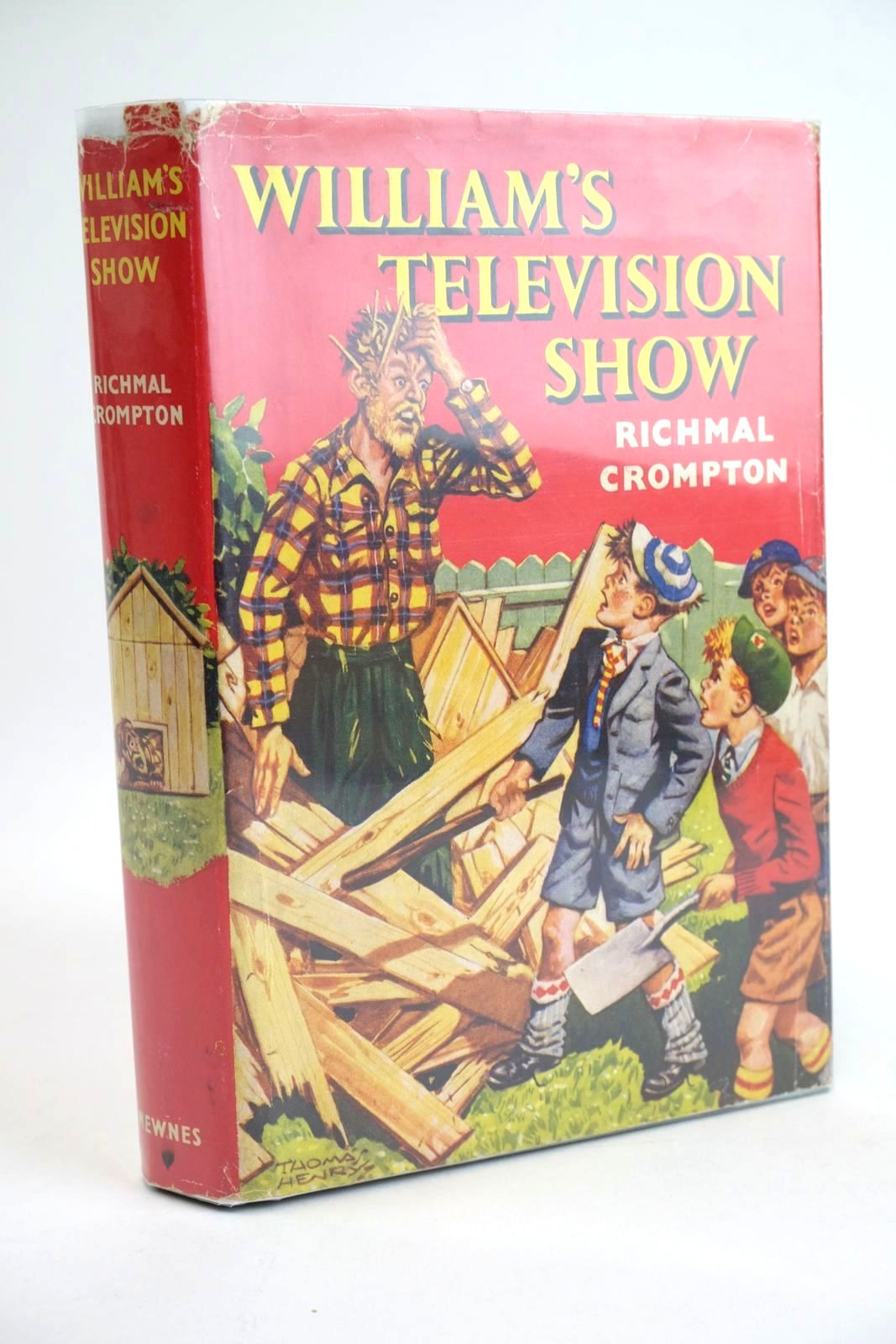

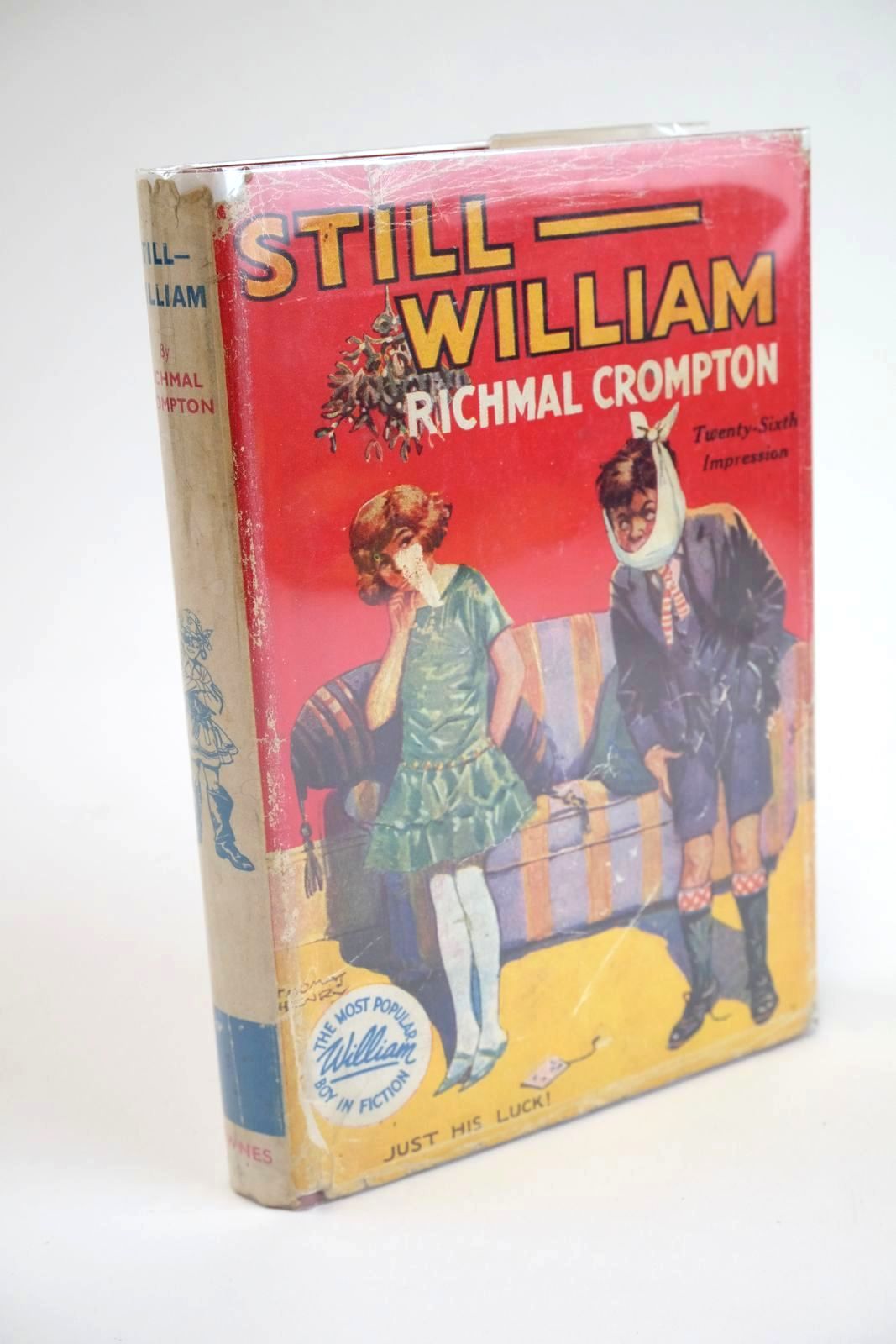

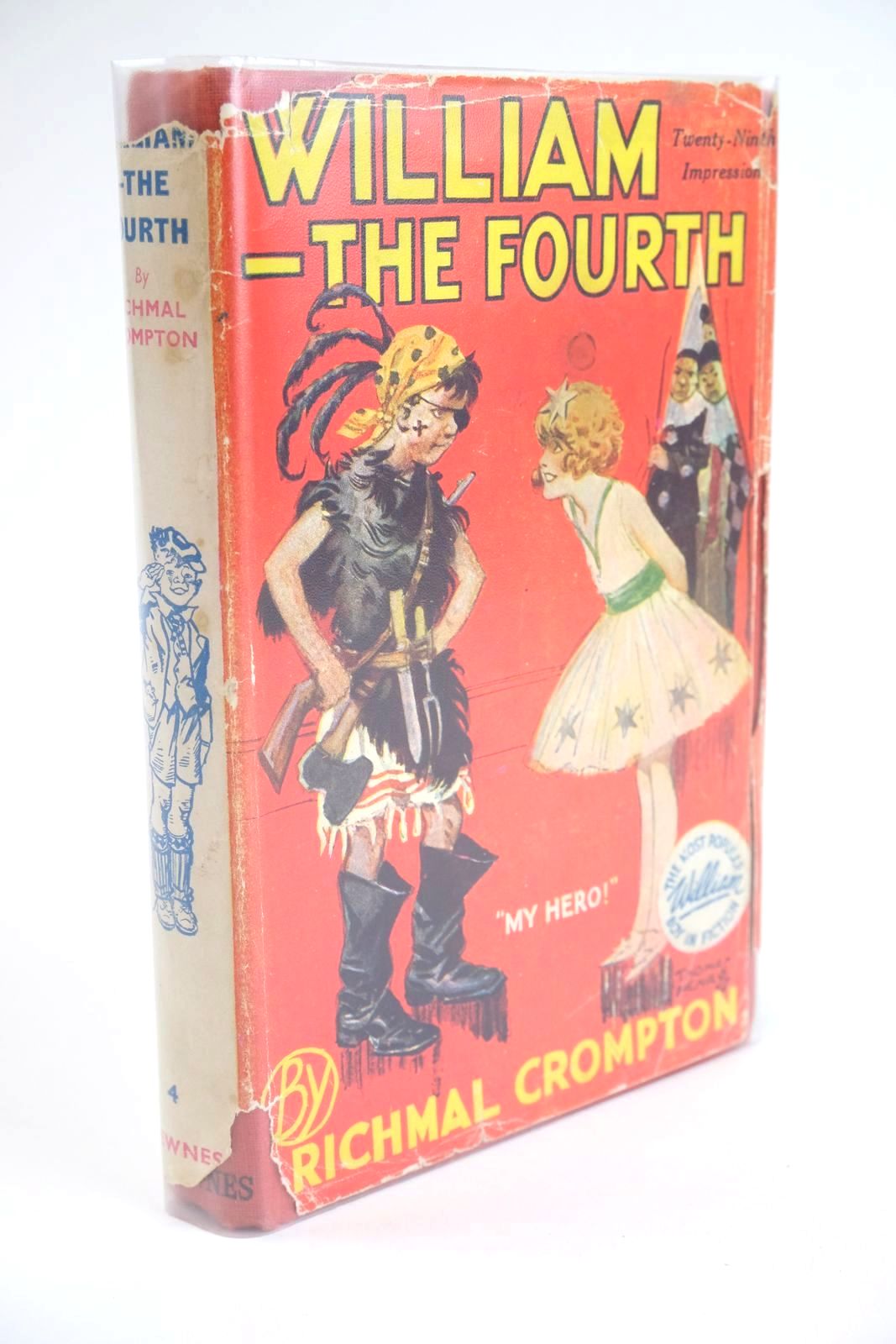

Another highly talented man - indeed, a man touched with genius - associated with the William series was Thomas Henry Fisher whose artistic vision so ably illustrated the series from its inception until his death in 1962. In him Richmal Crompton had the illustrator that she deserved – and no praise can be higher.

The new Macmillan’s Children’s Books edition of the first five books from the William series is the first in a long while that provides William with the setting he merits. Each book is solidly hardback with all the proper Thomas Henry illustrations in place and there is even the delight of a foreword by Richmal Ashbee (Richmal Crompton’s niece).

One word of warning though: do not give them to any children. Apart from the fact that they will mess them up with their sticky paws and their abominable habit of dog-earing the corners --- you will never get them back from the little so-and-sos.

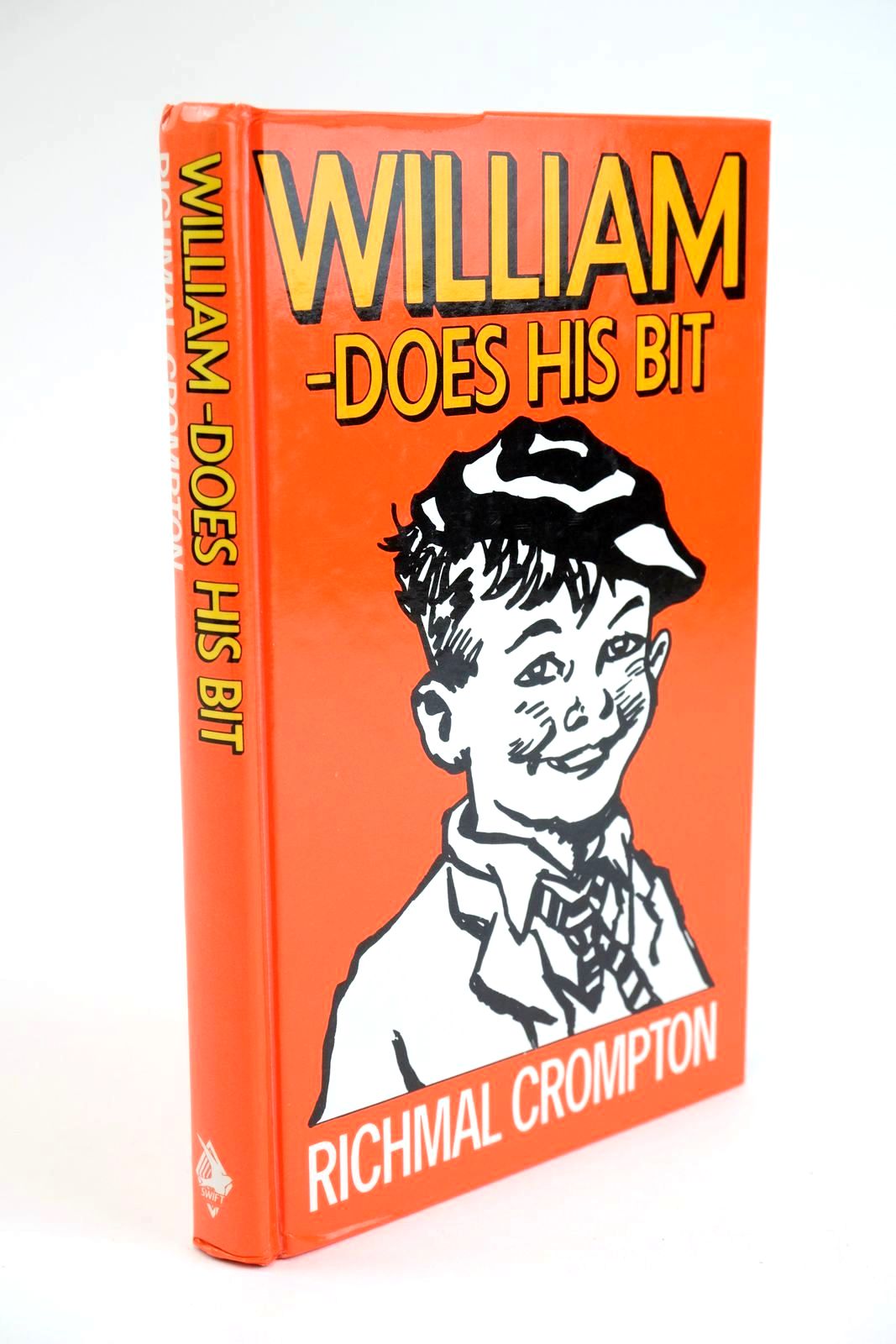

The final book (so far) of this series is a compilation of stories of William’s exploits during the Second World War. They have been especially selected by Richmal Ashbee.

Perhaps the best place to leave William is with the last story in this book. The War has ended and, in the Battle of the Flowers, William’s triumph over hisenemies underlines the nation’s achievement in overcoming the Nazi threat. Hubert Lane and co. have tried to trick William and the Outlaws into playing the parts of the defeated Nazis. With the aid of Violet Elizabeth the tables are turned and it is Hubert Lane and his gang that end up in that position. The watching adults completely misinterpret what is going on and assume the fight (as the enraged Laneites attack the Outlaws) mimics the ‘Battle of the Flowers’ in the pageant.

Perhaps the best place to leave William is with the last story in this book. The War has ended and, in the Battle of the Flowers, William’s triumph over hisenemies underlines the nation’s achievement in overcoming the Nazi threat. Hubert Lane and co. have tried to trick William and the Outlaws into playing the parts of the defeated Nazis. With the aid of Violet Elizabeth the tables are turned and it is Hubert Lane and his gang that end up in that position. The watching adults completely misinterpret what is going on and assume the fight (as the enraged Laneites attack the Outlaws) mimics the ‘Battle of the Flowers’ in the pageant.

Then, well fed, after a glorious tea of cakes, buns, jellies and sandwiches William and the elated boys go off to play rounders, triumphant and happy. William is in his element and, perhaps, catches something of those clouds of glory that Richmal frequently refers to.

“Jutht look at them,” said Violet Elizabeth, elevating her small nose. “Aren’t they dithguthting?”

“They haven’t any manners, boys” said Joan

Later William approaches them (his mouth full of chocolate cake)

“We’re goin’ to play rounders,” he said indistinctly. “Come on.”

Violet Elizabeth looked at him disdainfully.

“What a meth you’re in!” she said, “Joan and I don’t care for thothe childith gameth. We’re going to walk round the garden, aren’t we Joan.”

They walked off, arm in arm, without looking back.

William stood staring after them, baffled and crestfallen, pondering on the incomprehensibility of the female sex. Then he shrugged his shoulders, dismissed the problem, and ran to join the riot on the lawn...

For those who would like to learn more of the lady behind William, Mary Cadogan has written two splendid books.

‘Richmal Crompton: The Woman Behind William,’ is published by Sutton and the ISBN is 0750932856

‘The William Companion’ is published by Papermac at £10.25 and the ISBN is 0333511840.

Finally there is ‘Just Richmal: the Life and Work of Richmal Crompton Lamburn’ by Kay Williams published by Genesis. The ISBN is 0904351351.

Stella & Rose's Books wish to thank Mr. William Paterson for the kind submission of this article.

(Published on 30th Oct 2014 )