An Early History of Wine: from its origins to the Classical Period

"Noah, a man of the soil, was the first to plant a vineyard." Genesis 9.20-21

"Noah, a man of the soil, was the first to plant a vineyard." Genesis 9.20-21

Many have noticed the striking coincidence that Mount Ararat, where the Ark came to rest, is located where the cultivation of grapevines is believed to have originated - Transcaucasia, south of the Black Sea. However, even if one accepts the Biblical origins of viticulture, it is not necessary to plant a vineyard in order to produce wine. It is likely that early communities discovered the apparently miraculous transformation of grapes into wine when they first collected the fruit of wild vines: the berries will naturally, and quickly, ferment due to the presence of air-borne yeast on the grape skins. One wonders how these communities explained how grape juice acquired the intoxicating properties which seem to have caught poor Noah unawares - "When he drank some of its wine, he became drunk and lay uncovered in his tent."

Many have noticed the striking coincidence that Mount Ararat, where the Ark came to rest, is located where the cultivation of grapevines is believed to have originated - Transcaucasia, south of the Black Sea. However, even if one accepts the Biblical origins of viticulture, it is not necessary to plant a vineyard in order to produce wine. It is likely that early communities discovered the apparently miraculous transformation of grapes into wine when they first collected the fruit of wild vines: the berries will naturally, and quickly, ferment due to the presence of air-borne yeast on the grape skins. One wonders how these communities explained how grape juice acquired the intoxicating properties which seem to have caught poor Noah unawares - "When he drank some of its wine, he became drunk and lay uncovered in his tent."

Cultivation of domesticated grapevines had spread from Transcaucasia to Egypt and Greece by around 3500 - 2000 BC, and the Etruscans cultivated vines which had been present in Italy for thousands of years. After the 700s BC, the Greek colonists introduced more varieties around the Mediterranean coasts and into the south of Italy which they called 'Vine Land'.

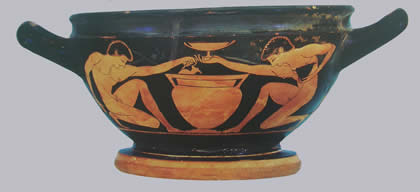

Although some may cruelly mock modern Greek wines for their lack of sophistication, in the Classical period Greek wines were highly praised. The Aegean Islands were the main exporters of wines, and Chios , followed by Lesbos, was considered to have the best wine. Wine was at the centre of the Greek symposium, and it was here that the curious practice of Kottabos developed. This was an early example of that popular phenomenon, the drinking game, in which participants would dextrously flick the dregs of their wine cups at a carefully balanced target. In fact, there were even teachers who would instruct the fashionable set on the finer points of wine throwing!

However, it was the Romans who gave viticulture possibly its greatest boost. As the Roman Empire spread around the Mediterranean and across Europe it carried new varieties and new techniques. An indication of the expansion in viticulture during the Roman Empire can be seen in the number of varieties described by the agricultural writers. Cato, writing in the third century BC, mentions only half a dozen, whereas Columella's twelve volume treatise two centuries later lists more than fifty varieties of grape.

It is Columella who provides us with the most technical information about Roman viticulture, while his contemporary the Elder Pliny , who had an eye for a good story, is happy to furnish more anecdotal evidence and urban legends. Pliny describes with relish the fortunes that certain individuals had made by investing in vineyards, as well as the carnival atmosphere that accompanied a particularly large vintage.

In contrast, Columella is more concerned with successful vineyard management. At the heart of his writing is an impassioned attempt to balance quality and quantity in a wine industry which was suffering from over-production and falling standards. As noted by Hugh Johnson, Rome was a big city with a big thirst and as growers pursued big yields the quality fell alarmingly. Columella's solution was to plant varieties noted for the excellence of their fruit, and then to increased yields carefully through diligent cultivation.

Although we may question the success of Columella's policy, two thousand years ago he was trying to answer a question which remains hotly debated today - is quality compatible with quantity in wine production?

Pictures from this article are taken from the book, The Story of Wine by Hugh Johnson.

Contributed by Tim Santon

(Published on 30th Oct 2014 )