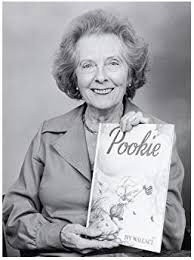

Ivy L. Wallace and Pookie

Stella & Rose's Books wish to thank Mr. John Gough for his kind submission of this article

Do you remember Pookie?

Author-illustrator Ivy L. Wallace’s Pookie was first published in 1946, when she was thirty-one. This and subsequent volumes in the series remained in print until I was working in a bookshop around 1970. Then they fell into an abyss. The original publishers, William Collins, decided not to reprint any of the Pooki” books, or Wallace’s other Animal Shelf series.Despite nearly thirty years of publishing success, Pookie and his creator have never been discussed in any children’s literature books or journals. Not treated seriously in their time, and no longer in print – when I first started researching Ivy L. Wallace and Pookie, around 1990 - things were looking pretty grim!

The Wikipedia article and the Daily Telegraph obituary for Ivy Lilian Wallace (1915-2006) explain that she was the daughter of a Scottish doctor, living in Lincolnshire. He was and a keen amateur botanist and entomologist. He would take her with him on his rambles in the countryside, teaching her the names of wild flowers, and encouraging her to paint plants in a botanically accurate way. (Look at the realistic painting of flowers in her illustrations!) As a child she started writing stories and drawing pictures, and her parents, recognising her talents, thought she might become an artist. However she became a successful actress, and when World War II started she joined the film-making department of the Ministry of Information.

Later in the war she joined the police. While working on a police switchboard, she doodled a picture of a fairy sitting on a toadstool with a little rabbit in front – it seemed that the fairy’s wings belonged to the rabbit. But she then decided that fairies were two a penny, so she erased the fairy and kept the little winged rabbit. She named him Pookie because “he had a little pookie face” and wrote his story.

“This is the story of Pookie, a little white furry rabbit, with soft, floppity ears, big blue eyes and the most lovable rabbit smile in the world.”

She illustrated her developing story with delicate, detailed watercolour paintings.

After war ended in 1945, she visited the publishing company William Collins & Sons in London without an appointment. She was turned away, crestfallen, but asked to leave her manuscript. A few weeks later she was contacted by William Hope Collins and asked to attend the Glasgow office where the Children’s Books section was based. She met William Hope Collins in the (now demolished) Cathedral Street offices and not only did William accept the book, he also fell in love with its author. Because he was already married at the time, and had children, their relationship met with shocked disapproval from their respective families and friends. But they eventually married in 1950 and went to live in house at Biggar, near the Scottish borders. They had two daughters.

Through the next twenty years, Wallace produced ten “Pookie” books, and used the stuffed toys from Pookie and the Gypsies to develop seven titles in the “Animal Shelf” series. She also wrote (but did not illustrate) four children’s novels featuring the five Warrender children in adventures that seemed loosely comparable to a blend of Enid Blyton and Edith Nesbit.

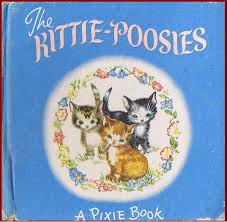

One small-format picture-story book for young children, The Kitty-Poosies (1951), was part of the popular children’s Pixie series of small books.

Wallace also published Baby Days: A Record Year by Year (1950, in either a PINK or a BLUE edition, with a gift box). This was possibly the first post-war book in which parents could record the details of a newborn child’s development.

Wallace also designed cards for The Medici Society, and published art prints, such as the 1950 picture of a mouse in a dress, with a shopping basket, on a pantry shelf.

Very quickly, the Pookie books were extremely popular. They were adapted to make radio programmes, and thousands of children attended Pookie rallies. Many of her books were translated into several other languages. (The Tale of the Kitty-Poosies, for example, became Mama Miezmau und ihre Kinder, in German. This translates loosely as “Mother Puss and her children”, or “Mamma Poorpuss and her children”.)

However, when her husband died in 1967, Wallace was heart-broken, closed her studio, and stopped writing and illustrating. Some years later, Collins stopped reprinting the Pookie books, and other Wallace titles, and for almost the next twenty years Wallace’s work was out of print and she and her books were severely neglected - but not completely forgotten.

Fortunately, Wallace was encouraged by a ceaseless stream of fan letters, and supported by her daughters, and in 1989 Wallace set about the task of rescuing Pookie. But she had to do this without the help of modern publishers or technology! She decided to set up her own publishing company, Pookie Productions Ltd.

By this time much of the essential original artwork had been lost at various printing companies around the world. This was an era shortly before computer-based digital scanning. The graphic reproduction machinery that was used around 1990 needed artwork on flexible paper rather than painted on rigid artboard. Recognising the reproductive challenges, Wallace decided that new paintings were needed, on suitable flexible paper, faithfully following the old art no mean feat for a woman by then in her mid-70s.

(Perhaps later editions may be able to use computer graphics to fully restore the original freshness of the first versions of Wallaces’s painting, in the same way that early versions of Mary Tourtel and Alfred Bestall’s “Rupert Bear” comic strips and annuals are renewed for modern printing by teams of computer-aided graphics technicians. When Wallace set about recreating the original illustrations she lost, in my opinion, some of the freshness and lightness of touch in brushstroke and ink drawing.)

Naturally the reissued stories remained the same, on the whole. However, Wallace told me (in a letter from this time, around 1990) that she intended revising Pookie and the Gypsies, an exciting story of capture and rescue which connects Pookie’s world with the stuffed toys of the Animal Shelf series.

Why revise? In Britain, “Gypsies” are now better known as Travelling People (or Romany), and circuses with caged animals are no longer politically correct. As Wallace said of modern developments in printing, “Time marches on … with no respect for winged rabbits! Pookie and the Gypsies will take some thought & replanning if it is to come out again as Circuses are not ‘in’ things now here Gypsies are ‘Travelling People’ no caged animals, etc. (I’m a supporter of ‘no cages’ of course!) I’ll be re-writing it & re-illustrating something to take its place as no. 10 in the series”.

(Despite this, interestingly, Ludwig Bemelmans’ Madeline and the Gypsies (1959) was happily reprinted with no revision at all!)

The re-publication (with renewed artwork) of the “Pookie” books was a runaway success!

Interestingly, reviving the original “Animal Shelf” stories, led very quickly to the creation of the television animation series based on Wallace’s characters and some of her actual “Animal Shelf” books.

Many great authors, and author-illustrators, and artists, go through a period of struggle, then success, and then – usually posthumously – neglect, and – then, perhaps eventual rediscovery and fresh appreciation. (A good example of this is Alice Duer Miller, one-time prolific and author, poet, dramatist, screenwriter, and creator of The White Cliffs – a best-seller verse novel of World War II, later made into a very popular Hollywood film.)

As fashions change, what had once been fashionable falls into disfavour, and is considered old-fashioned. But later, often, what had fallen out of style is revalued by younger eyes and minds, not just from nostalgia, but because the good qualities that were originally recognised and praised are seen afresh, and appreciated again always within the large context of changing tastes and styles. Usually the rediscovery of supposedly “old-fashioned” artworks and books occurs posthumously: few authors and artists live long enough to see their ageing work re-appreciated.

Ivy L. Wallace was unusual in being the creator of both her first success and later, after decades of neglect, re-creator of her own reappraisal and rediscovery, during the 1990s and early 2000s within her own lifetime! Remarkable!

Now I want to consider some of Wallace’s books in detail.

The first story, Pookie, is a charming version of the Ugly Duckling theme presented in a traditional talking-animal fairy-tale tradition. Pookie “lived with his Mother and Father and four brothers and sisters, deep down in the warm brown earth under a great Oak tree, and had lettuce and honey sandwiches for tea every Wednesday, and two hazel-nuts for pocket-money every Saturday”.

Inevitably almost any later “rabbit book” owes something to Beatrix Potter’s many rabbits and Alison Uttley’s Little Grey Rabbit. And Wallace admits the name Pookie was probably influenced by her childhood love for Milne’s “Winnie-the-Pooh”. But Wallace’s Pookie, while working within identifiable traditions, is an original character within a well-respected canon. Like Enid Blyton’s Noddy (who was not published until 1949!), Pookie even makes up little songs.

Unfortunately, by the second paragraph we discover that Pookie is unhappy, because he is little, white, full of bounce in the night when little rabbits ought to be sleeping and he has “two silly, flimsy, filmy, wispy wings sprouting out of his back!” He doesn’t fit in at home. At first his wings are seen as something unnatural and shameful. He is forced to wear them wrapped tightly in ribbons. He dozes through Mr Owl’s school in the day. Then, waking in one special moonlit night, Pookie sees fairies (with wings!) dancing and flying, and longs to join them. He even believes, or hopes, that he might actually be a moon-fairy himself.

But the Moonfairies and Goblins laugh at him when he tries to dance with them in the moonlight, and Pookie falls flat on his face as his wings don’t allow him to fly. No wonder Pookie packs a small bundle in his best handkerchief and leaves a note: “Gon to ceek mi fourchune. Wiv luv from Pookie”. Pookie is simply responding to Mr Owl’s sarcastic advice Pookie - doesn’t even know what a Fortune looks like!

This leads him to meet a variety of woodland creatures, including gnomes and pixies, along with ordinary rabbits, owls, and so on. Just as Enid Blyton's classic character Noddy meets Big Ears, Pookie meets Nommy-nee the Elf, who offers him somewhere to stay. The full-page picture of the Pixie market is beautifully detailed, along with the narrative explanation of the clothing and food sold at the market. Wallace makes honey buns sound absolutely delicious! But Pookie is disheartened by the characters he meets who belittle him for his wings and he is still unable to fly.

The pictures clearly belong in the classic fairy tale tradition of Arthur Rackham, Mabel Lucy Atwell, and William Heath Robinson. Large friendly trees have knobbly faces, fairies swirl through dark skies, goblins and elves live amongst flowers and toadstools close to the earth. Through word and image Pookie’s world is richly realised. For me as a child reader there was perfection evoking a sense of C.S. Lewis’s “longing” (described in his delightful 1955 autobiography Surprised By Joy) in sticky buns, burrows under trees, satin-lined sewing baskets, carrots, honey and lettuce sandwiches, Goblin Markets, and overalls with straps. The quest and character growth, with attendant desperate adventures, which occur in Pookie are presented at precisely the very young child’s level fascinating, terrifying, brief and, at last, heart-warmingly resolved.

At the darkest moment of Pookie, as winter approaches, and Pookie faces starvation, still not having found his fortune (whatever that may be), the sad little winged-rabbit resolves to throw himself off a hillock. But the gentle wind takes him, and by (happy) chance he is rescued by Belinda, the woodcutter’s kind daughter. Nurtured by Belinda, Pookie finds that, when he is loved his wings grow and strengthen, and he is able to fly. Pookie ends, like Hans Christian Andersen’s “Ugly Duckling”, with Pookie finding a happy permanent home, and a cosy bed by the fireplace, sleeping in Belinda's satin-lined needlework basket.

If Pookie had been the only book by Ivy L. Wallace, she would be, or should be, remembered as a great author-illustrator for this book alone.

Perhaps the best of the Pookie stories, which, after the first, the “origin” story, form a series rather than a connected narrative sequence, is Pookie Puts the World Right (1949). Despite the title, this is not a political tract, although in this, and later Pookie books, Wallace shows significant environmental awareness.

When the first rough winter storms blow through Pookie’s woodland home, terrible damage is done. Angry that winter has come early, and caused harm for his friends in Bluebell Wood, Pookie shouts to the storm,

“Winter! … Can you hear me? I think you are cruel and wicked! You come too early and spoil all the berries and nuts with your frosts and snow! And then the Woodland folk go hungry until Spring comes! Then you stay late in Spring and spoil all the early flowers and fruits! And you are so rough … you smash trees down, and little homes in them come crashing down too! Winter, I wish you would go away and never come back!”

Pookie’s bravery succeeds. Winter goes. But the victory is hollow.

Pookie must learn that, with all his terrifying faults, Winter is part of the balance of life. Moreover, some of his friends were careless in their choice of homes that were shown to be vulnerable to a natural storm. Pookie has dared to disturb the universe, and must take responsibility (a big word for a little rabbit). He must be braver still, attempting to put the world right again.

This is one of the great lessons of George Macdonald’s mystical classic fantasy At the Back of the North Wind (1870), grappling with questions of cause and accident, and nature’s indifference in a casual capricious world. It is the natural world’s equivalent to the fundamental human issue of the existence of evil in the world. Although Wallace had never read Macdonald (as she told me, in a letter), her achievement was to put this lesson in terms that could make sense to very young children. Such a lesson for her British readers is equally pertinent to readers living in the temperate coastal regions of Australia, and pertinent also to those living in regions where the seasons are Wet and Dry, where snow never falls, where the cruel monsters of nature are drought, flood, cyclone and fire.

Yet, for all that the lesson is clear and touching, it is free of didacticism. Pookie learns because the story naturally requires it.

Pookie and the Gypsies (1947) is the second “Pookie” book by Ivy L. Wallace. At the end of the first book, simply titled Pookie (1946) Pookie, despairing, is rescued by Belinda, the kind daughter of a woodcutter. The second book is a rescue adventure of a different kind, as the title and cover illustration suggest Pookie is seen sitting on a high tree branch, looking down on the bright tents and caravans of a circus.

Perhaps surprisingly, even though, as a character, Pookie has barely been introduced, this story also introduces a separate sequence of characters and animals, the “Animal Shelf”, which later became a successful children’s TV cartoon series.

The story begins when Pookie sets out from Belinda’s cottage very early one morning, to “fly to the end of the wood and back”. Just when he feels it must be breakfast time, and flies down to land on a tree, he sees the circus not that Pookie understands what a circus is, at first. A gypsy walks out of one of the tents, and puts a small monkey on another branch of the same tree, chained to the branch.

Naturally Pookie begins to talk with the monkey called Tunkey and he is shown some of the monkey’s circus tricks. Alas, as Pookie is concentrating on watching Tunkey, the gypsy catches Pookie and puts him in a cage. But Pookie is not alone. Also in the cage is another captured animal, a stuffed-toy giraffe, who has lost some of his stuffing, so he continually falls over, and is told to “get up” naturally, and amusingly, the giraffe is called, or believes his name to be, Getup.

Getup, and another stuffed-toy a zebra called Stripey belonged to a boy called Timothy. But Timothy’s mother had sent the two toys to a jumble sale (perhaps a church bazaar, or a fete). Although the two toys had escaped on the journey, Getup was captured by the gypsy, and is now part of the circus act.

Another creature also visits the caged animals: Kinker, the mouse, so-called because his tail was once caught in a mouse-trap and, although he managed to get out of the trap, his tail was permanently kinked. Perhaps because of the trauma of this injury, Kinker does not talk, but Getup is able to “read” what Kinker tries to communicate, by observing Kinker’s face and eyes.

The gypsy realises that a flying rabbit will be a great attraction at the circus. At first Pookie does amaze the crowd, and is thrilled to be the centre of attention. But when Pookie considers a thrilling life in the circus, he remembers Belinda, and feels so crippled with homesickness that his wings almost completely shrink and he is no longer able to fly.

The gypsy is so annoyed that his star attraction has stopped being an attraction he decides he will put Pookie in a pie!

Happily Stripey comes to the rescue, and all the animals escape. Pookie offers them a home with Belinda. But Getup and Stripey choose to return to their loving master, Timothy. (Later, and never again with any connection with Pookie, the two stuffed-toys Getup and Stripey, and a different monkey called Woeful, and two other toy animals, a bear called Gumpa and a tiny white kitten called Little Mut (spelled with one “t”), appear in a series of small-book format stories – “The Animal Shelf”.) Tunkey and Kinker both choose to return to the circus. As Tunkey explains, at the circus there are “special nuts and bananas which might not grow in the wood”, and there is the happy circus life – “I love being in the Circus” despite which Tunkey has his usual sad monkey face (hence, similarly, the name of the “Animal Shelf” toy monkey, Woeful it is how that sort of monkey naturally looks).

Naturally Pookie is delighted to be reunited with Belinda, safe, and at home, loved, and a little wiser.

This may not be a masterpiece of children’s literature, such as Pookie, or Pookie Puts the World Right, but it is a thoroughly satisfying story.

I doubt that Pookie and the Gypsies was re-illustrated, revised, and reissued in the last years of Ivy L. Wallace’s life. When she wrote to me about her struggle to recreate the artwork so that the “Pookie"” series could be reprinted around 1994 she said (about the possible re-issuing) “Pookie and the Gypsies will take some thought & replanning if it is to come out”.

Should we be concerned? In 1947 who (apart from Travelling People or Romany, or however they would refer to themselves) would be concerned at the word “gypsy”? (Political correctness, surely, only goes so far in an historical work, and usually does not act retrospectively. We are unlikely to start referring to pieces of gypsy-inspired music such as Sarasate’s “Gypsy Airs” or “Zigeunerweisen” as “Travelling People’s Piece” or “Roma Melodies”.) Similarly, animals in cages, and animals as circus acts, and even animals in cages in zoos, were just the way of the world around 1947. A simple Note to the Modern Child could explain that things are, happily, different now. In my opinion, Pookie and the Gypsies, unrevised for would-be political correctness, in its 1947 telling, is simply a good story, plainly told in the language of the time.

A more important question is whether there is any racial prejudice in the description of the actual gypsy who features in the book? He is described as “a tall dark man with gold rings in his ears” (in the first un-numbered page of the story). But surely this is merely descriptive, not prejudiced. His behaviour may seem cruel: keeping Tunkey chained up, and caging Getup, and then Pookie. Certainly he does not feed them well “a plate of brown mush that tasted of nothing, and a tin lid of water”. Unquestionably he is brutal when he decides to turn Pookie into a rabbit pie. But, in his defence, he has no need to keep a rabbit that is not a performing circus attraction. (His disappointment is reminiscent of the dashed hopes at the end of the classic Warner Brothers cartoon “One Froggy Evening”, directed by the great Chuck Jones: 1955 a frog that can SING AND DANCE on a sidewalk when no one else is watching, but that merely croaks when put on stage!)

Far more significantly, given a chance at freedom, Tunkey and Kinker both choose to return to the circus and the gypsy. He can’t be that bad, surely! The man may be dark in complexion, and have ear-rings (very fashionable, nowadays!), and a bad-temper when disappointed, and lack sensitivity to animal nutrition, but he is not a bad man. Nor is there compelling evidence of racial or ethnic prejudice in the story.

As the key beginning of the “Animal Shelf” series, and as a fine addition to the tales of Pookie, with excellent illustrations, and a circus story almost as good as Walt Disney’s Dumbo (! – which contains caged animals!), Pookie and the Gypsies is highly recommended.

Other Pookie titles include adventures, dreams, and simple occasions such as birthdays, Christmas, the early life of a nest of swallows, and a trip to the sea. Pookie in Search of a Home presents the more serious issue of the cost of “progress” when humans attempt to build a road through Bluebell Wood. (This is an environmental issue related to one of the themes of Roald Dahl’s first book, The Gremlins, a picture-story book published in 1943.) As with May Gibbs’ earlier Gumnut stories, and Mary Norton’s later Borrower stories, humans are capable of being either good or bad in Pookie’s world, forcing young human readers to consider themselves as humans, and their allegiances to other humans, animals, and the world.

Wallace’s “Animal Shelf” series, initially linked briefly to Pookie by the Gypsy adventure, belongs in the stuffed toy tradition that sprang from A. A. Milne and ranges now from Margaret J. Baker, Barbara Softly and Joan Robinson, to Martin Waddell and many current authors. The creatures of the Animal Shelf belong to Timothy, a real boy.

Gumpa is a well-worn lazy teddy bear. Woeful is a sad-faced little monkey (who looks just like Tunkey, an actual monkey in the gypsies’ circus). Stripey is a stuffed-toy black-and-white striped zebra. Little Mut is soft and cuddly but always in trouble, and Getup is the giraffe who is losing stuffing from his hooves and is always falling down hence, “Get up!” There is also a real mouse (not a stuffed toy) called Kinker, who lives with the gypsy circus, has trouble with a pet shop, and visits the Animal Shelf toys. Kinker once had his tail caught in a mouse trap, resulting in the eponymous “kink”.

The stories in the “Animal Shelf” series are much shorter than those in the “Pookie” books, naturally – fewer pages, smaller pages, and much fewer words. Pookie, of course, is the hero every time, whereas in the “Animal Shelf” books, different characters take centre stage in different books, and often interact like siblings within a family as the friends of the Animal Shelf undertake an everyday activity such as a picnic, or a walk in the woods. The overall feeling is more of an ensemble, broadly similar to the multi-character stories in A.A. Milne’s “Christopher Robin” books. Some of the stories focus on the animals preparing for a special event, such as Timothy’s birthday – the animals decide to prepare a surprise picnic – or acting out something that has occurred in their life – Timothy has been reading them the story of Robinson Crusoe, and the animals go outside to play about being shipwrecked, and Getup becomes, accidentally, castaway, and lost. It is easy for younger readers, or, more likely, young children having these stories read to them, to identify directly with the pretend-play activities of the Animal Shelf friends.

Although it is a stand-alone book, The Kitty-Poosies (1951), is possibly Ivy L. Wallace’s story and book that most resembles those of Beatrix Potter. I knew The Tale of the Kittie-Poosies as a child. Eventually, time and younger siblings wore the original family hard-cover into a raggedy tangle of torn pages and ageing cellotape (scotch tape). But for a long while I did not connect this simple, short, and tiny-format picture-story book with the wonderful quarto-size “Pookie” books, also by Ivy L. Wallace.

Later as an adult I found, by lucky chance, a Collins “Pixie Library” paper-back reprint, and I was delighted to have a brand new copy, this time called “The Kittie Poosies”.

The Tale of the Kittie Poosies resembles the great Beatrix Potter’s stories of cats, such as The Tale of Tom Kitten, with its genteel mother cat, and some well-behaved female kittens, and a rambunctious boy kitten. As with Potter’s own father-less cat family, Ivy L. Wallace’s cat family have no hint of a “man of the house” but maybe that is the way of cats, and of rambunctious toms.

Once upon a time in a little pink house with a blue front door there lived a little cat. Her name is Mama Pudditat. She is a tabby cat with soft silky fur. Isn’t she a lovely cat?

(I will ignore the almost certain coincidence between her surname and the classic way the Warner Brothers’ cartoon Tweety bird refers to Sylvester – “I tawt I taw a puddytat!” What is baby-talk for Tweety is almost certainly a Scottish brogue for Wallace, who probably never saw a “Tweety and Sylvester” cartoon, or paid it much attention, before writing the book, around 1950.)

In fact, there are TWO beginnings, depending on the edition. The FIRST edition starts like this:

Not very far away there is a little pink house. It stands in its own garden, in which grow all sorts of flowers. It has a blue front door and one chimney. There is a lantern to light on dark nights. // Do you know who lives in it? (Obviously the second page introduces …)

Incidentally, the German version is part of a German “Pixi Bücher” series, the translation of the story uses the original version: Nicht weit von hier steht ein kleines rosa Haus. E steht in einem wunderhübschen Garten mit herrlichen Blumen. …”

Effortlessly we glide from the once-upon-a-time past tense in the first sentence to the immediacy of the present tense, and we can SEE exactly what the story tells us, because on the left of the un-numbered first page there is a picture of Mama Pudditat, at her front door, dressed in a sober tight-bodiced full-length Victorian gown with a lace collar, protected by a neat white apron, shaking out a dusting cloth, about to collect the pint bottle of milk left on her door step, with a rose on her left, and a fox-glove on her right.

Would you like to see inside the house?

[And we turn the page].

This is the kitchen … Mama Pudditat likes baking. Here she is busy making pies. It’s a funny oven, isn’t it? But it cooks well.

And the double-page illustration shows Mama Pudditat rolling out pastry as she stands at a bright blue wooden table, decorated by a stencil silhouette of a mouse, with a row of silhouettes of pink mice (naturally) decorating the hem of her window curtains, and tiny pink mice decorating her crockery on a high shelf. An opened tin of sardines rests on the floor, beside a mixing bowl. (This book is a young child’s visual delight!)

The next double-page spread shows clever Mama Pudditat painting a blue silhouette mouse to decorate a green wooden stool in her sitting room, where the glow of the fire is cosy even though the actual fire is only hinted at.

Mama Pudditat is then visited (past tense, suddenly) by Mrs Pattypaws.

They eat kipper sandwiches, and lap milk from saucers. (Naturally!)

Then they tip-toe upstairs to see the new Kittie-Poosies.

(This titular word “poosie” may seem odd: but almost certainly it reflects Wallace’s own, likely, or borrowed Yorkshire or Scottish? accent.)

“OH!” whispered Mrs Pattypaws; “The dear wee pets! What are you going to call them?” But that [the story tells us] is another story.

(Incidentally, here the word “pet” does not mean the domesticated household animal of a human owner. It is used as a natural term of affection.)

And suddenly this tiny picture-story book turns into a CHAPTER-BOOK because when we turn the page, that “other story” begins, with a chapter heading, “Choosing Names”.

I will try not to spoil too much of the pleasure of name-choosing. What would YOU call a grey kitten with white paws, or a ginger kitten the colour of toffee, or a third kitten that purrs?

The un-numbered third chapter introduces the drama:

Mama Pudditat was very worried. The kittens were eating so much now [their eyes had opened, and they were growing fast, as kittens do] there was not enough money to pay the bills. “How can I make some money?” mewed Mama Pudditat.

Suddenly she had an idea.

“I shall need sugar and cotton and paper bags and paint, and a piece of wood and a hammer and nails!” she said.

What CAN Mama Pudditat’s idea be?

(There is no father in the house, and similarly no hint of money-making BEFORE the arrival of the new kittens. But isn’t that the way of many children’s books. Characters LIVE without having to MAKE a living unless it becomes an element in the plot, as it does, here.)

It is easy to imagine the eager curiosity of the young child who is happily sitting in an adult’s lap, watching the pictures as the pages turn, and hearing the direct appeal of the narrator to the listener. This book draws you in! What CAN Mama Pudditat’s idea be?

I will reveal no more. The idea is a great success, and the pictures are simply DELICIOUS!

It is a pity that Wallace created no other small-format Pixie series titles. She did, however, write stories for yet another Collins series of books, My Book of Kittens and Puppies (Collins

Wonder Colour Books series: 1954). But perhaps she was too busy to provide illustrations because these stories are illustrated by Racey Helps, himself a prolific author-illustrator of children’s picture-story books in those years, but without the runaway popularity of Wallace’s “Pookie” or “Animal Shelf” series.

We may get a sense of the realistic (but Blytonian) adventures in the four “Warrender” books by considering no more than the dust-jacket “teasers”.

The Young Warrenders

The first exciting story in which the Warrenders make a simple decision which has the most unforeseen consequences and draws the children into a mystery as sinister as it is baffling. You will want to know if their come out on top.

Strangers at Warrender’s Halt

The Warrenders invite six unknown young people for Easter to their rambling old house in the country and trigger off another fast-moving mystery adventure. You will laugh, thrill, be puzzled, and at last rejoice with the resourceful five.

Thanks to Peculiar

The Warrenders plunge headlong into an adventure which for Derry and Di, especially, is to prove the most hair-raising of their lives. And it all started when Di missed the bus picnic.

The chapter-titles of The Young Warrenders also show the kind of story this is: 1. Family Council 2. House to Let 3. Enter the Mallings 4. The Warrenders Prepare 5. The Mallings Pay a Visit 6. The Day on the River 7. The Barbecue 8. Binkie is Lost 9. Derry and Di Disobey 10 Binkie Remembers 11. Beech Tree Lookout 11. An Astounding Conversation 13. Do on her Own, …

The illustrations (at least for the first “Warrender” title) are effective realistic colour-plates and ink drawings by Joseph Acheson.

I will not make a case for the “Warrender” books to be reissued, but invite anyone else who wants to pursue this to investigate further.

Finally, amongst all her own writing, and author-illustrating, Ivy L. Wallace was also the illustrator for at least one other author: Marjorie Barrows Jo Jo, Rand McNally, Chicago, 1964 – a book written by an American (presumably), published by an American company, illustrated by an Englishwoman, about an Australian koala!

Contributed by John Gough

References and Further Reading

Gough, J. 1996. “Pookie Flies Again” Classroom vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 40–42.

Wallace, I.L. Pookie series: 10 titles

Pookie (1946)

Pookie and the Gypsies (1947)

Pookie Puts the World Right (1949)

Pookie in Search of a Home (1951)

Pookie believes in Santa Claus (1953)

Pookie at the Seaside (1956)

Pookie’s Big Day (1958)

Pookie and the Swallows (1961)

Pookie in Wonderland (1963)

Pookie and his Shop (1966)

Animal Shelf series 7 titles

The Animal Shelf (1948)

Kinker visits the Animal Shelf (1948)

Woeful and the Waspberries (1948)

Getup Crusoe (1948)

The Huge Adventure of Little Mut (1949)

Gumpa and the Paint Box (1949)

The Treasure Hunt (1951)

Young Warrenders series 4 titles

The Young Warrenders (1961)

Thanks to Peculiar (1962)

Strangers at Warrender’s Halt (1963)

The Snake Ring Mystery (1966)

Other books

Baby Days: A Record Year by Year (1950)

The Kitty-Poosies (1951)

My Book of Kittens and Puppies (illustrated by Racey Helps: Collins Wonder Colour Books series: 1954)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivy_Wallace

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1514475/Ivy-Wallace.html

https://www.scotsman.com/news/obituaries/ivy-wallace-1-488075

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Animal_Shelf

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Ivy-L.-Wallace/e/B07DDKZTHD

(Published on 10th Oct 2018 )