The Lure of Speed

The Lure of Speed by Henry Segrave, Published by Hutchinson in 1928

Sir Henry Seagrave, an early pioneer in the world of motor sport gives a fascinating insight into early 20th century motor racing. He explains that in 1928 when this book was written that motor racing is much safer than when it started the century before, even though casualties occurred at virtually every race! He talks about racing past, present and future describing with a sound technical sense and in detail his record of a unique racing career over eight years, and the story of his life with modesty and restraint. His recall for all the events he entered is amazing, listing the state of the track, the problems before and during the race and who won or lost.

It is astonishing to read, that the principles of the sport have changed very little in the last 100 years. Seagrave started when the sport was in its infancy and participated in both road racing and sprints and eloquently describes the conditions the drivers had to put up with. Races were over long distances on public roads, so the surfaces were anything from dirt to tarmac and dust was an ever present nuisance. He illustrates this with Gabriel’s feat in the Paris-Madrid race of 1903. Apart from the race being stopped because of so many fatalities, Gabriel averaged over 65 miles an hour in his 70 horse-power Mors car for the distance of 342 miles. He overtook many cars and for the greater part of the distance he travelled in a white cloud of dust that was so opaque there was nothing to guide them but the scarcely visible tops of the trees.

It is astonishing to read, that the principles of the sport have changed very little in the last 100 years. Seagrave started when the sport was in its infancy and participated in both road racing and sprints and eloquently describes the conditions the drivers had to put up with. Races were over long distances on public roads, so the surfaces were anything from dirt to tarmac and dust was an ever present nuisance. He illustrates this with Gabriel’s feat in the Paris-Madrid race of 1903. Apart from the race being stopped because of so many fatalities, Gabriel averaged over 65 miles an hour in his 70 horse-power Mors car for the distance of 342 miles. He overtook many cars and for the greater part of the distance he travelled in a white cloud of dust that was so opaque there was nothing to guide them but the scarcely visible tops of the trees.

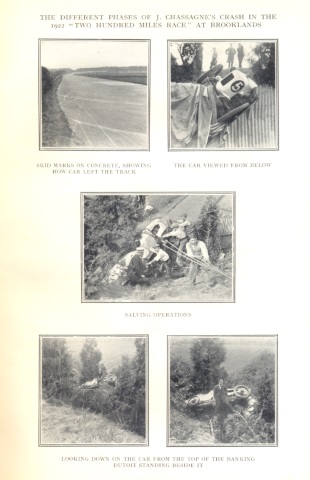

Seagrave devotes chapters on speed, accidents and the future of motoring. They are full of reason and common sense. Accidents were a very big part of racing and early on it was usually the mechanics that were killed. They used to be in the car with the drivers so they could mend the car en route, and they were invariably thrown out of the car. The driver had the steering wheel to hang to and if he kept his head and hung on rather than throw himself out, nine times out of ten he would survive! Seagrave has his own theory as to why Ascari died in 1925 as he knew Ascari, his car and the corner where the accident happened and he was participating in the race. It is fascinating to read firsthand accounts of such historical events. He knew all the main players and seemed to have witnessed most of the tragic events of those times.

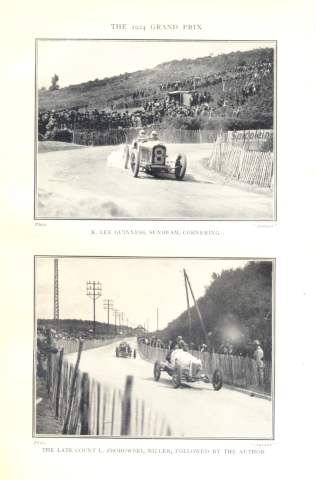

A Grand Prix event is described in detail and, although it is similar to today, it is very different in the organization and lead up and also the hands-on approach of the driver. There was not a pre-arranged calendar as today since there were only a handful of Grand Prix, mainly taking place in France and the UK. Only when the location was decided by invitation could personnel and drivers go the tracks to inspect and sort out the car set up and accommodation. Once the cars were complete from this gathered information, testing was required at the track before the drivers then drove their cars to and from the Grand Prix!

A Grand Prix event is described in detail and, although it is similar to today, it is very different in the organization and lead up and also the hands-on approach of the driver. There was not a pre-arranged calendar as today since there were only a handful of Grand Prix, mainly taking place in France and the UK. Only when the location was decided by invitation could personnel and drivers go the tracks to inspect and sort out the car set up and accommodation. Once the cars were complete from this gathered information, testing was required at the track before the drivers then drove their cars to and from the Grand Prix!

Henry Seagrave also participated in land speed records and seems to cross from one discipline to the other with ease.

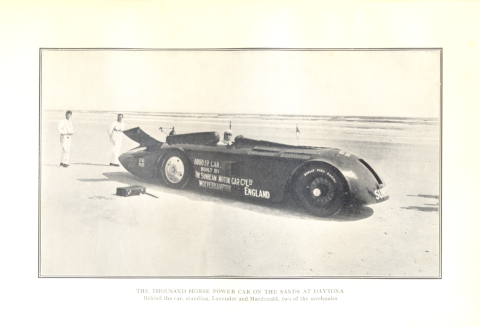

His desire was to achieve 200 miles per hour which even today is fast. He had already set the record over a kilometer at Southport with a 33 hp. 12 –cylinder Sunbeam, but, as he says, the figures were scarcely registered and had been replaced. There were already three cars in France and Britain that on paper were able to do 150 mph using aircraft engines, Captain Malcom Campbell being one of them. So in 1927 a 1000 hp engine was decided on and ingeniously they split the engine in two, half at the front and half at the rear. Seagrave’s ‘Patron’ worked out a rough design of the car and handed it to engineer Captain Irving to build. The other big problem was the tyres and this was down to Seagrave himself to sort out. He went to the Dunlop Rubber Company who were very interested. It took several months and much expense to develop and test on a special rig to be sure the tyres would be safe at 200mph. There were many unknown quantities that had to be dealt with and allowed for but they made it to Daytona Beach, Florida.

His desire was to achieve 200 miles per hour which even today is fast. He had already set the record over a kilometer at Southport with a 33 hp. 12 –cylinder Sunbeam, but, as he says, the figures were scarcely registered and had been replaced. There were already three cars in France and Britain that on paper were able to do 150 mph using aircraft engines, Captain Malcom Campbell being one of them. So in 1927 a 1000 hp engine was decided on and ingeniously they split the engine in two, half at the front and half at the rear. Seagrave’s ‘Patron’ worked out a rough design of the car and handed it to engineer Captain Irving to build. The other big problem was the tyres and this was down to Seagrave himself to sort out. He went to the Dunlop Rubber Company who were very interested. It took several months and much expense to develop and test on a special rig to be sure the tyres would be safe at 200mph. There were many unknown quantities that had to be dealt with and allowed for but they made it to Daytona Beach, Florida.

(photographs on page 208)

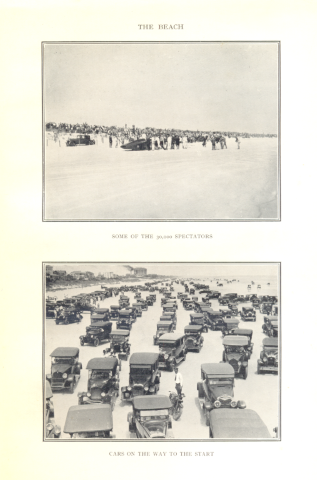

They were met by many press reporters on their arrival at New York and there were 15,000 people on the beach to watch the attempt. Seagrave was the first person to set the record at 203.7 mph but he is convinced that the car could have gone faster as, in his opinion, unnecessary changes had been made to the car. His recollections of the attempt were very hazy and he describes more of trying to control the car than how he was feeling. He pays tribute to the two fearless men who had absolute faith in their own engineering ability, and in the fact, hitherto believed impossible, that a speed of 200 mph with safety on land was capable of being realised.

They were met by many press reporters on their arrival at New York and there were 15,000 people on the beach to watch the attempt. Seagrave was the first person to set the record at 203.7 mph but he is convinced that the car could have gone faster as, in his opinion, unnecessary changes had been made to the car. His recollections of the attempt were very hazy and he describes more of trying to control the car than how he was feeling. He pays tribute to the two fearless men who had absolute faith in their own engineering ability, and in the fact, hitherto believed impossible, that a speed of 200 mph with safety on land was capable of being realised.

Henry Seagrave was quite aware that after all this hard work and preparation, this record would undoubtedly be broken, as it was by Malcom Campbell.

With all these descriptions the author gives a fascinating insight as to what racing was like in those days and you can easily imagine how difficult, but also thrilling, it must have been.

Contributed by Bernice

(Published on 8th Sep 2020 )