Sugar-Plums and Sherbet – The Prehistory of Sweets

Sugar-Plums and Sherbet – The Prehistory of Sweets by Laura Mason

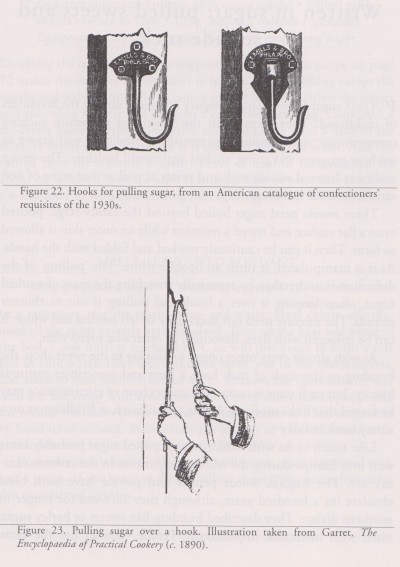

Sweets. We all like sweets and ate them as children. I remember it was a special treat to go to the shops to buy some sweets and then having to choose from the rows of jars. It was not easy! Sherbet was my favourite, but I don’t seem to be able to find it anymore. That is part of the history of sweets in that they have changed and been reinvented over the years. The term sweets to me means boiled sweets such as humbugs, barley sugar, seaside rock and jelly types such as jellybeans as well as marshmallows. It seems though that we use the term to include just about anything sweet such as chocolate, fudge, liquorice, puddings and desserts. Chocolate only became a competitor to sugar confectionary after about 1850. The confusion arises where its uses were overlapping: a medicine, preserving agent and spice. Do you know how they get the letters into seaside Rock? How they twisted barley sugar? The difference between fudge and tablet?

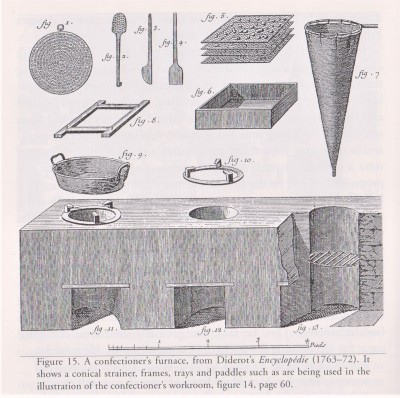

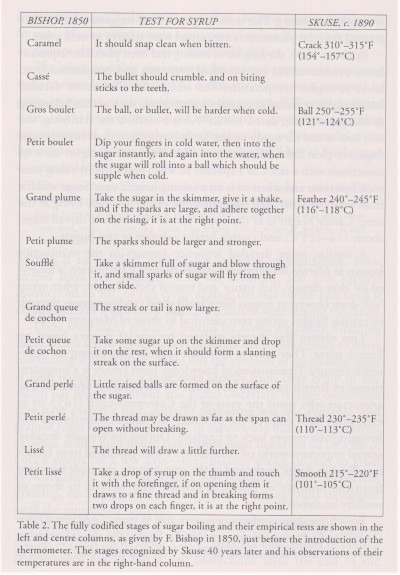

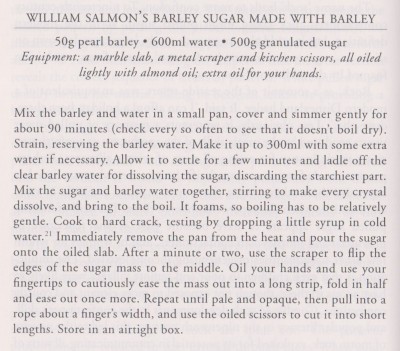

Sugar boiling is a special skill by which confectioners work syrup through a series of transformations. There is a helpful discussion of the technicalities of sugar-boiling as foundation for a history of individual sweet types.

This spills the beans on the methods used by early confectioners to put the layers into gobstoppers and the stripes into humbugs.

As well as a history, it is also a recipe book. There are twenty tried and tested methods for sweets ancient and modern, including tablet, fudge, toffee, sugar plate, acid drops and many more.

But when were they invented? Amazingly the first written recipes have been around since the sixteenth century. These earliest recipes for sugar-working in English come from manuscripts, not printed books and have their roots in medieval medicine and alchemy.

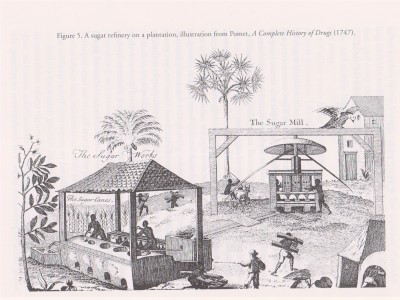

How and when did sugar arrive in Britain? Sugar-cane is thought to have been cultivated in New Guinea and to have diffused to various Asian countries, including India in prehistoric times. In the centuries since classical antiquity, sugar and Islam travelled together to permeate the Mediterranean world. In England, early records of imported sugar show that it came from Morocco, Cyprus and Alexandria. Sugar production then moved progressively westward. In the fifteenth century cultivation of cane expanded to the islands of Madeira, the Canaries and Sao Tome. Development of sugar plantations soon followed when the Portuguese began to grow sugar in Brazil and British development of plantations began in the Caribbean from the mid-seventeenth century onwards. During the Napoleonic wars, sugar beet was developed in Europe as a rival to cane sugar. Napoleon saw the advantage to be gained from home-produced sugar and, from 1813 onwards the French really developed the industry. Beet became steadily more important and by the First World War, Britain was importing sugar from eastern Europe. By this time, it had passed from luxury to bulk commodity

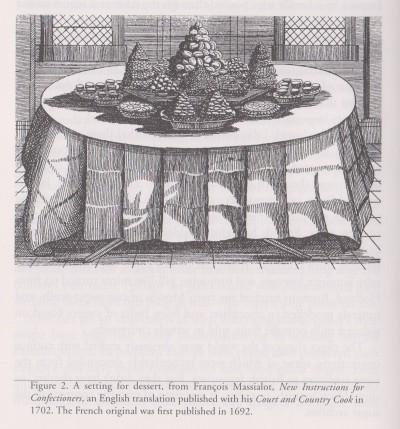

And how did Britain, a country which could not grow sugar-cane, chocolate or spices, come to be one of the most important global producers and consumers of sweets? The obvious answer is trade and empire. These were vital to the expansion of the industry, but more obscurely our medieval ancestors saw confectionery as a high-status, luxury consumer product, with the added advantage of a healthy image. (/Figure 2 page 20)

In trying to understand the history of sugar boiling, Laura Mason has written a detailed and interesting history from those first early recipes to the industrialization of manufacture a hundred years ago.

Contributed by Bernice

(Published on 14th Jul 2021)