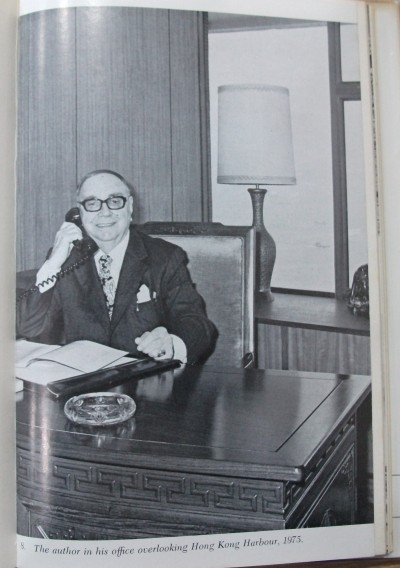

The Ocean on a Plank By Captain W. A. Doust CBE

The title of this book intrigued me. What did it mean and what was the book about as the title does not make it clear?

This is the autobiography of Captain Doust who spent most of his working life on the sea. His area of expertise was marine salvage where his engineering skill and his amazing ability to improvise, with whatever equipment was available, under the most difficult of circumstances made him a master of his profession.

He was born in Portsmouth in April 1895 into a strong nautical family background. Both his grandfather and father were Royal Navy engineers, so whatever his career it would be to do with the sea.

Doust got into the salvage business through the accident of Turkey lining up with the Central Powers in 1914. Aged 19, at the request of his good friend Lt-Commander Arthur Truscott, he sailed his fifty-four-foot ketch to Constantinople with two others. After two stormy months they reached their destination. Truscott was recalled to England and war was declared. Doust spent the war on an estate and lake of the Gulf of Ismid.

When the war was over, aged 23, he joined the Navy as an acting temporary sub-lieutenant. His first job was on the Bosphorus and then Crimea. He was phased out of the Navy soon after and, having learned a great deal about towing, he got work with the Ocean Salvage and Towage Company. He learned every salvage job, particularly the system of propellor-dredging called ‘scouring’, much used in seas where there are very small tides and consequently little natural lift. He perfected his craft and eighteen years later, having gone as far as he could, he accepted a job with The Salvage Association at Lloyd’s as one of their special officers. He moved into a house in Datchet on the River Thames with his wife and son.

For the next seven years Doust travelled the world using this knowledge, proceeding immediately when necessary to wherever the distressed or endangered vessel might be. On arrival he would advise the underwriters of the damage, the possibilities of eventual salvage and whether the operations were being professionally carried out. This was all valuable experience, and it paid off as, in all the cases he dealt with, each with its individual problem, he never had a failure.

Doust’s account of his work for the Marine Salvage Department of the Admiralty during the war throws much new light on a sadly neglected but vital aspect of our struggle to maintain naval supremacy. When war broke out, he had already joined the Admiralty in Whitehall with the rank of Commander. His function was that of Salvage Advisor in the recreated Marine Salvage Department of the Admiralty. He spent the next four years setting up the department with the much-needed personnel and equipment as well as designing a lifting craft which would ‘wriggle anywhere’ and lift 800 tons. Once America joined the war, much needed equipment could be sought. Not only was he able to improvise, but he was also adept at getting things done via the back door. His most audacious success was ordering fire-fighting pumps from the mayor on behalf of the Admiral and First Sea Lord without going through his officer first. The pumps were destined for a ship that was sinking 320 miles out to sea. He got away with it and the ship was salvaged successfully.

By 1942, with an OBE under his belt, Doust was losing patience with office routine and wished to get afloat once more. One Saturday morning a signal came in that altered his war, giving him the chance to jump out of the Admiralty. A salvage officer was being returned from Algiers and a top-ranking salvage officer, with the organizing ability to grasp the magnitude of impending operations, was being looked for as a replacement. In his usual style Captain Doust put himself forward by sending a signal that he was ‘flying out forthwith’! Once reaching Algiers he was re-united with Sully, his American counterpart, and had no sooner settled in when there was an urgent signal that a nine-inch lifting wire was to be sent from Algiers to Malta, for which British authority was required. There followed, as Captain Doust says, a daft, night long episode of trying to track down the wire and get it onto the destroyer.

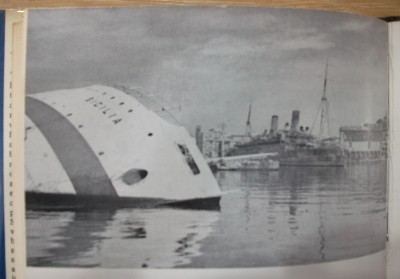

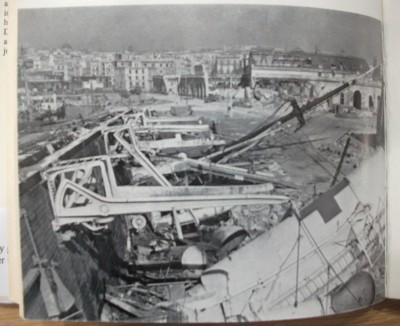

From there he was sent to Sicily and then, on 2nd October 1943, to Naples where the destruction was immense. In his words, ‘In their vindictive lust for destruction, the retreating Germans had polluted the water supply, destroyed the pasta factories, even burned the city’s archives. They had set fire to every useful building in the port area. Every quay space was blocked, the harbour filled with every imaginable wreck.” When surveying the harbour, he and Sully stopped counting at 150 - these were the only visible wrecks sticking out of the oil film. Six months later, with the help of some 150 Italian divers and other key specialists, the port was cleared and described as a classic example of fine cooperation between British and American forces. Doust received a CBE, and the Americans honoured him with the Legion of Merit.

In August Doust was sent to Hong Kong via Singapore. He sailed aboard a destroyer from Ceylon, crossing the Indian Ocean in a world at peace. He had been on active service from the first day of war to the last and the only scratches he received were from hypodermic needles!

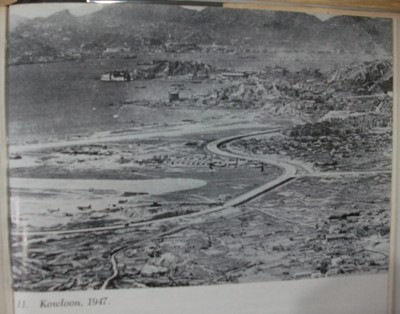

Although the world was at peace there was still a lot of salvage work to do. The port at Singapore did not have much damage - just five ships sunk in the harbour - as the atomic bomb had stopped the Pacific war where it stood. No diver would work for them however as the basin was infected with sharks! He left personnel to sort it out and found a destroyer to take him to Hong Kong, little realizing that he would spend the rest of his life there. Hong Kong had been occupied since Christmas 1941 and the harbour and waterfront had taken a terrible pounding. The preliminary survey indicated about 230 wrecks of all kinds, including sixteen large ships. It was difficult to work on and keep the momentum going though, as many of the men wanted to go home, but by February 1946 Doust was able to confirm that the majority would be cleared by the end of the year.

This was a transition period between wartime and peacetime usages and Doust recognized the old enemies of paperwork and pessimism, but there was an infectious vitality about Hong Kong which was very much to Doust’s taste. He bought a large house and having complied with the instructions to stay in the service until the port was operational, he joined the Navy to clear two wrecks in the Naval Basin. Once cleared he was discharged on 17 December 1946.

The New Governor asked him to become Salvage Adviser until the last of the wrecks were removed. He accepted as it gave him time to arrange his future in Hong Kong. The first was to get his son Rodney to join him. Rodney was also in the salvage business, and Doust had not seen him since 1942. It took two years to clear the harbour and created a booming business with rolling mills and the salvor vessels for hire.

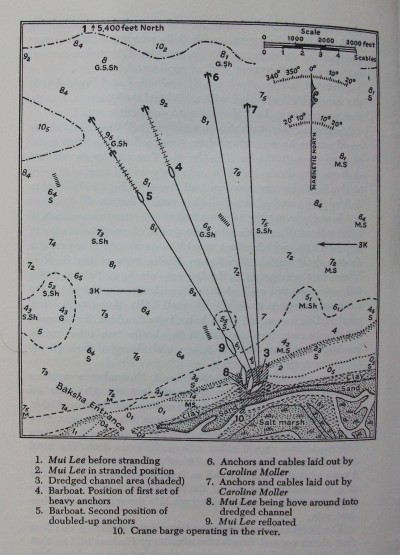

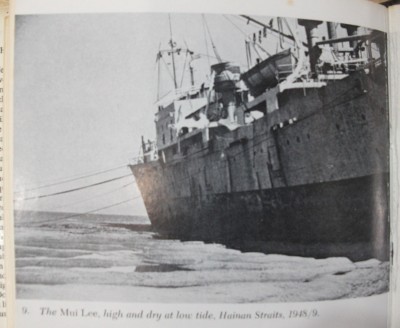

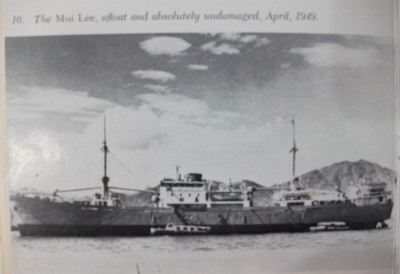

Doust then went to work for Moller’s, the biggest and oldest salvage and shipping company in the area. He has included, in his book, the arbitration document for the longest and hardest job he had in peacetime, giving the reader a very clear picture of how a salvage company makes money and why it earns it. In September 1948 a Norwegian motor ship was stranded during a typhoon. The rescue operation took eight months, tied up five ships and their crews and cost over £90,000. She was refloated without any damage and Captain Doust felt immense satisfaction at the fruit of so much hard work and frustration. This along with many other stories in this book give a detailed account of the salvage business and how Captain Doust operated within it.

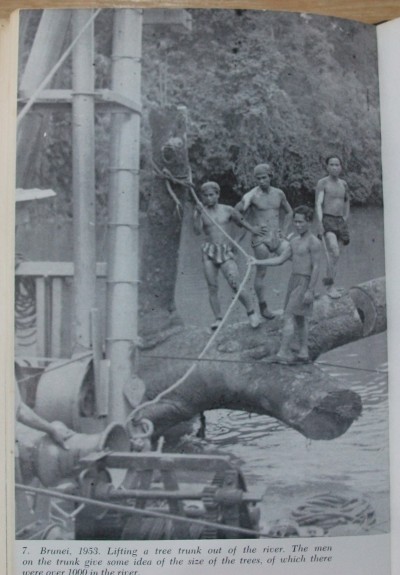

In 1950 Doust branched out on his own with the Suens, who he had looked after for their father, Admiral Ma, in Shanghai. Their first venture did not go well but their luck turned, and they were on the up and up, enabling them to move on to the biggest and most interesting project. It was a commission to make the Behait River, which formed the boundary between Sarawak and Brunei, navigable. This was a big job as they were to clear away the thousands of trees growing in the riverbed, demolish unwanted banks and make a hydrographic chart of the river for 85 miles from the mouth. He and the labour force spent 18 months on an accommodation pontoon, clearing, dredging, dumping and firing as they went, leaving the sultan of Brunei with a river whose navigational depths were now known and mapped.

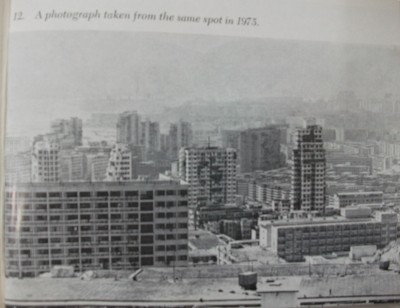

From there Doust broke into the marine construction business and spent three years building the breakwater and typhoon shelter at Aberdeen, on the southern coast of Hong Kong island, before undertaking the biggest and most lucrative project – that of enlarging Kowloon using a dredger to fill in the shallow inlets. The dredger, bought by the Governor, unfortunately sunk in a typhoon but, unperturbed, the Governor said to fill the inlets by land instead. This worked just as well as terraces were cut to fill in the bays, so land was gained in the hills as well.

At 80 Doust was still working, fit and enjoying life, but leaving the active location work to his Chinese partners. This is a precis of his working life, but the interesting aspects I enjoyed are his descriptions of some of the many salvage jobs he was involved with, not that I understood all of it! But also, his talent for improvisation with often very little resources especially during the war.

And the meaning of the title? It is from a Chinese proverb: ‘When the Deities protect you, it is possible to cross the ocean on a plank of wood. Without their help you may drown in a wayside ditch’

Contributed By Bernice

(Published on 14th Sep 2024)