Picturesque Description of The River Wye By T.H. Fielding

Those of you who are familiar with our shop, Stella & Rose’s Books, know that it sits on the bank of the River Wye in Tintern, separated from the river by the main road running from Chepstow to Monmouth. A beautiful location with views over to the majestic ruins of Tintern Abbey. While the Lower Wye Valley is a popular destination for tourists, how many know of the journey the river takes before arriving at the River Severn beyond Chepstow? This book enlightens us.

Published in 1841, Picturesque Description lives up to it name, not only in the text but also the 12 glorious hand-coloured tipped-in aquatints.

The source of the Wye as described by Fielding rises “amid lofty wilds, and for many miles retains the mountain character; it then glides through a more level, rich and fertile district; and afterwards bursting through a barrier of immense rocks, it forces its circuitous way between high precipices, till it meets, and is hurried back, by an impetuous tide, that rises to a height almost unknown to other streams.”

The Severn and the Wye issue from almost the same spring, high up of the side of the mountain of Plynlimon, the highest point in mid-Wales and where folklore says there is a sleeping giant! Fielding is not impressed with the countryside surrounding the river source, describing the wolds as “dreary and desolate: they enclose numerous solitary vales, or hollows, and are frequently intersected by ravines, where the only sound that greets the traveller is the mournful croak of the raven, or the melancholy whistling of the winds, which blow down savage glens, rendered still more wild by the hoarse rushing of the mountain torrent.”

Fielding goes into some detail about the conquests of Owen Glendour (sic), a Welsh leader, soldier and military commander in the late Middle Ages, who led a 15-year-long Welsh revolt with the aim of ending English rule in Wales: “It was near the head of the Wye, not withstanding the inclemency of the air, that Owen Glendour for some time took up his station, and whence he ravaged the surrounding country”.

On entering Radnorshire, Fielding tells us, “the landscape becomes much more agreeable”, the scenery being “both picturesque and grand”. There follows a description of the town of Rhayader, or “Rhayader-Gwy, i.e. the Cataract of the Wye, so called from the falls in the river at this place, which though low, seem to have been thought of sufficient consequence to give a name to this town”.

Beyond Rhayader the river winds its way through towns and villages, all interestingly described, until reaching the town of Hay in Brecknockshire. Fielding is rather scathing about Hay stating that “It is poorly built but a spirit of activity prevails there”. “The town of Hay was defended by a castle and walls, that were both destroyed by Owen Glendour. Some remains of the castle may be seen, converted into a dwelling.” Owned since the 1960’s by bibliophile Richard Booth, famed for turning Hay into the first international town of books, the site was purchased in 2011 by Hay Castle Trust and is today a popular destination, being a major centre for culture, arts and education.

At Hay the river enters the county of Hereford. Fielding spends some time describing the city of Hereford, the Cathedral, the Cloisters and the monastery of Black Friars. Further on “the Wye receives the waters of the river Lugg, the most important auxiliary of all its tributary streams… The Wye and the Lugg unite their streams near the village of Mordesford; and tradition informs us that a winged serpent was accustomed to resort to the spot where this junction takes place, to slake the thirst caused by the indiscriminate slaughter of men and animals.”

Now the river flows past Ross, Goodrich and Monmouth, with Fielding providing fascinating descriptions of the history of these towns and villages and then we arrive at Tintern, the home of Stella and Rose’s Books and of course Tintern Abbey, founded in 1131 by Cistercian monks. While acknowledging that “as a beautiful picture, the ruin, and the accompanying scenery, leave little to be desired”, Fielding tempers this with “unless we might wish for the removal of the dirty cottages and black manufactories of the iron forgers, that disturb the original quiet and elegant simplicity of the place”. Needless to say, with the demise of the Tintern industry and wireworks in the 19th century, we no longer have “dirty cottages” or “black manufactories”. Instead Tintern has been nicknamed “Little Switzerland” in reference to the beautiful scenery surrounding the village.

On a quiet day weatherwise, at low tide, the river meanders around the village and, looking at it, one could not imagine that it could rise 20 feet in just a few hours when the tide races in from the Bristol Channel. Add to that a south-westerly wind and conditions are ripe for the river to flood the road and on occasion the houses and shops on the river bank, including ours. Fortunately, we are aware of the tide times and used to weather watching, so are usually prepared with flood boards, towels and mopping up equipment!

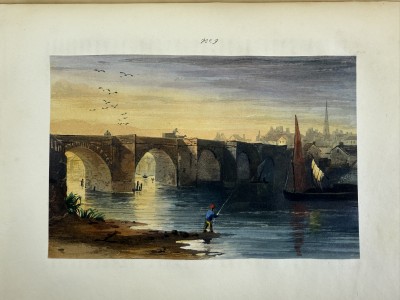

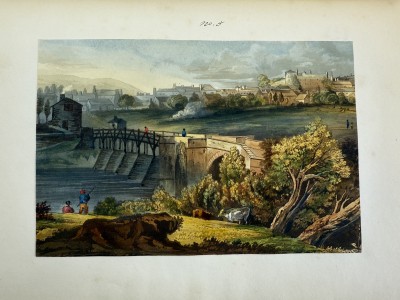

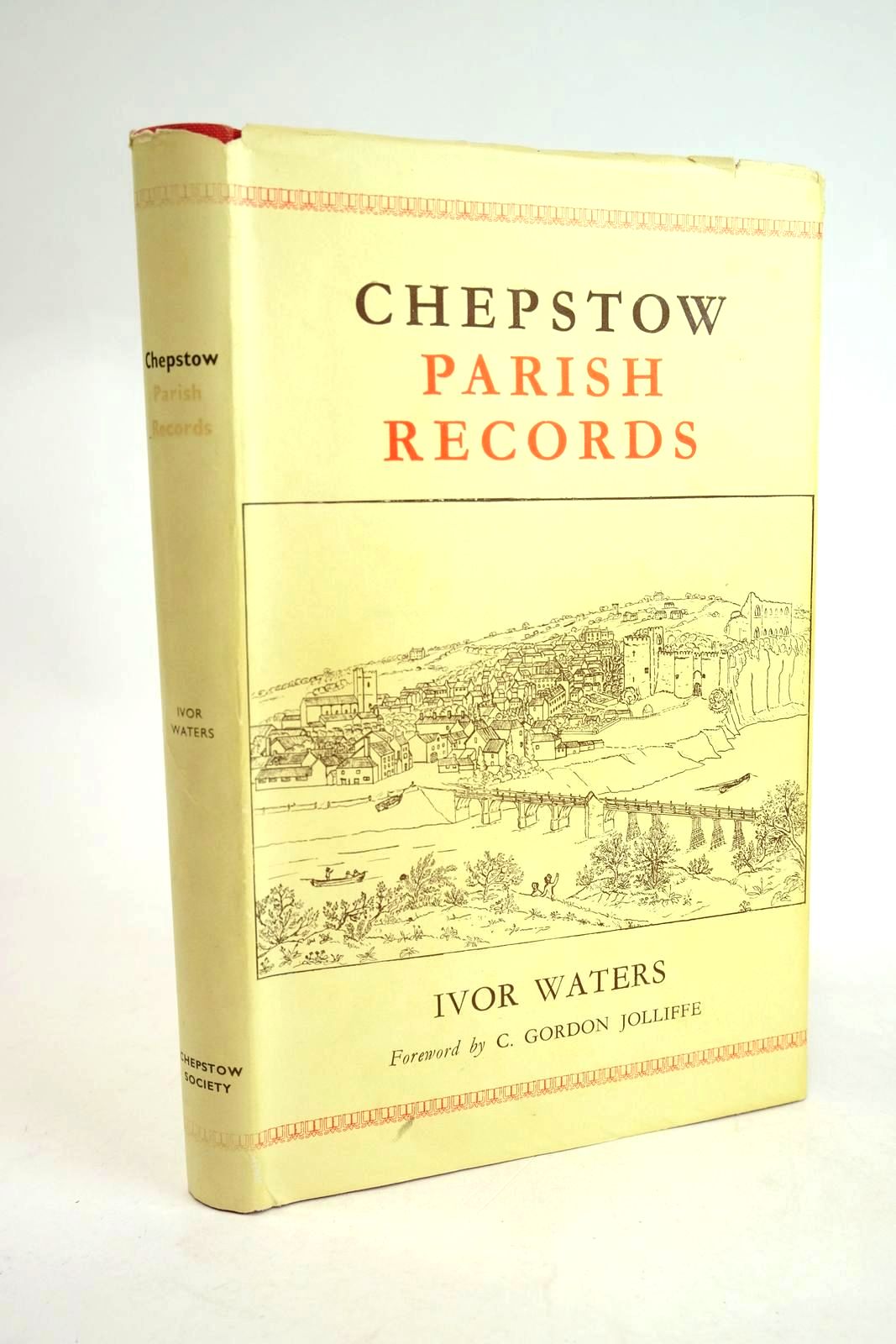

The River Wye ends its journey at Chepstow where it eventually “mingles its waters with the impetuous tides of the channel of the Severn.” Fielding goes into great detail of the history of Chepstow Castle which he declares “is one of the grandest remains of feudal power in the island”.

I can do no better than leave you with Fielding’s description of this most beautiful area of Wales: “From hence [the village of St Arvans] the river is seen, flowing down and immerging from a steep valley, that suddenly opens to the sea, with powerful combinations of subject. Bold fore-grounds of the most vigorous forms; ranges of extensive woodlands, stretching over the undulating lawns, or hanging down the ravines, ingulfed between towering cliffs; the reaches of the river, stretching forward, in the middle distance, by the bridge, the shipping, and the town of Chepstow; the latter of which rises from it banks, crowned with the huge towers and embattled ramparts of the Norman fortress, that hangs on the verge of the cliffs, and seems to form part of the native rock; the whole linked into one picture by the glorious burst of landscape beyond, where an extensive arm of the sea received the confluent waves of the Wye and the Severn; over which the eye wanders to the distant horizon, as it follows the retiring lines of the blue lands of Somersetshire.”

Contributed by Chris

(Published on 19th Nov 2024)