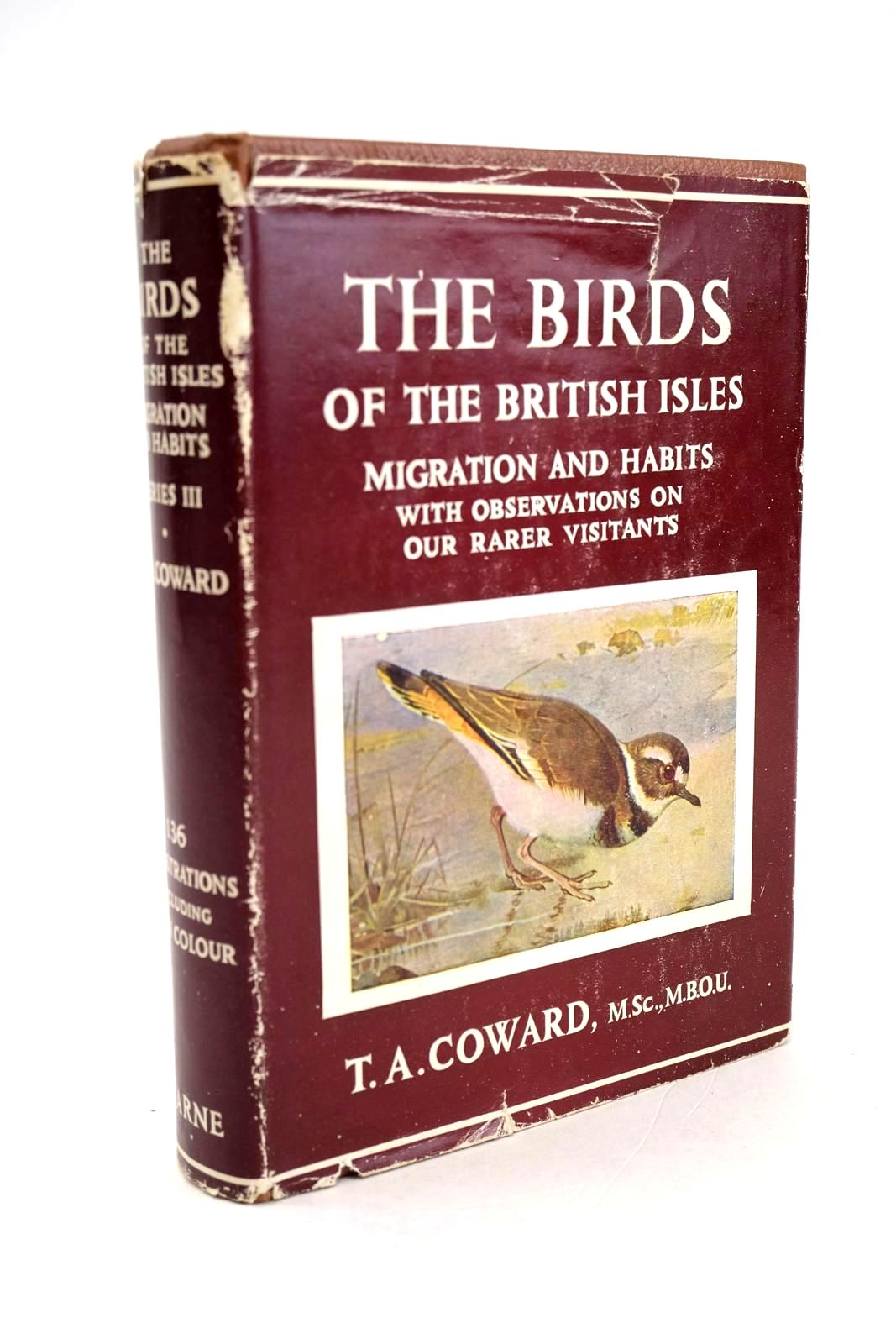

The Observer’s Book of British Birds

The Observer’s Book of British Birds by S. Vere Benson

Stephana Vere Benson. It seems people are not sure if Stephana was her name as she never published it as such on the title page. The Misses Benson began the Bird-Lovers’ League firstly amongst their friends and neighbours and subsequently it grew to more than thirty thousand members worldwide over the next fourteen years.

This book was first published in 1937 and is the first of the Observer’s Series. There are at least 15 different dust wrapper variations for the book, published by Frederick Warne and Co. Ltd. Some with only minor changes. The book was revised in 1952, 1956, 1960, 1965 and 1972. The book contains one bird per page, making it an excellent reference guide.

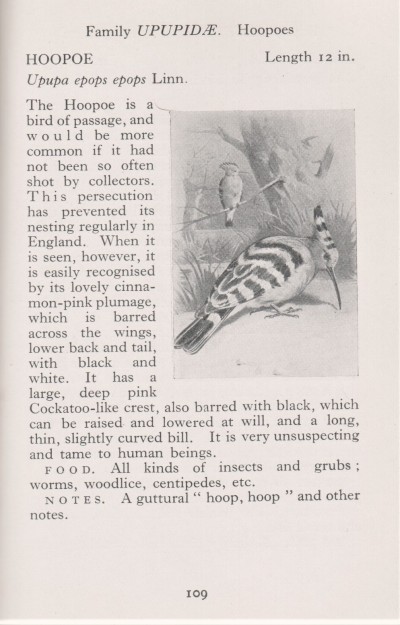

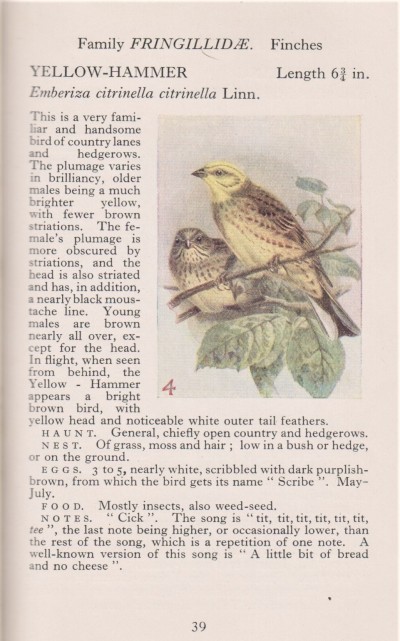

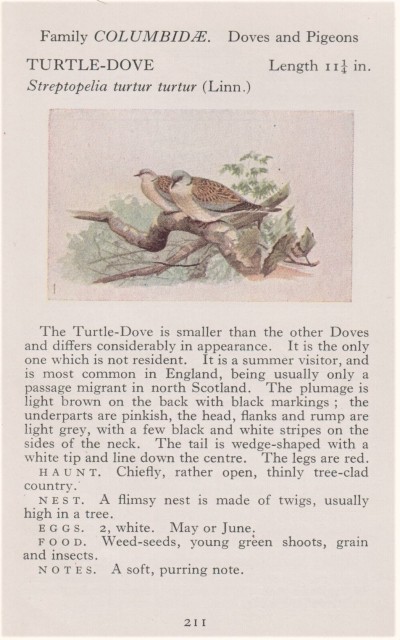

The beautiful illustrations are reproduced from Lord Lilford’s work ‘Coloured Figures of the Birds of the British Islands’ drawn by Archibald Thorburn and other well-known artists.

The author writes a very insightful preface which chimes excellently with the attitudes of today towards the wonderful world of birds and wildlife.

She begins by saying: ‘The publication of this little book is the fulfilment of a long-cherished hope.’ This was to create a book that was ‘neither too bulky, too expensive or inadequate to the needs of the would-be ornithologist.’

She continues by saying: ‘The true ornithologist or bird-lover is he who observes without interfering with or marring what he sees’.

Evidently there were those in society who collected bird skins and eggs. Miss Benson says: ‘Personally, I consider the bird-lover who cannot tell a Sparrow from a Kingfisher more worthy of admiration and emulation than the unscrupulous collector.’

She also gives excellent tips regarding bird identification saying: ‘The greatest aids to identification are general shape, flight and notes’ (notes here meaning song). There is also a diagram to show the parts of the bird.

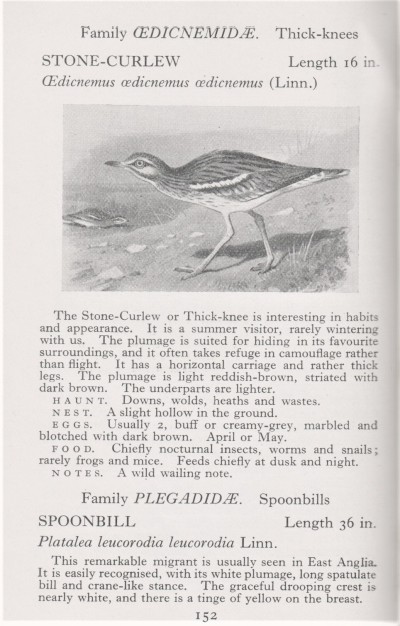

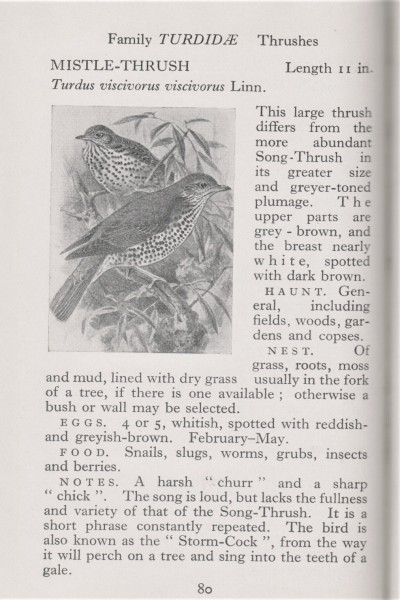

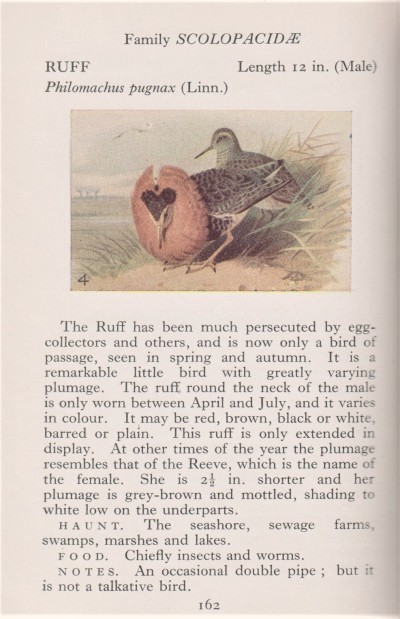

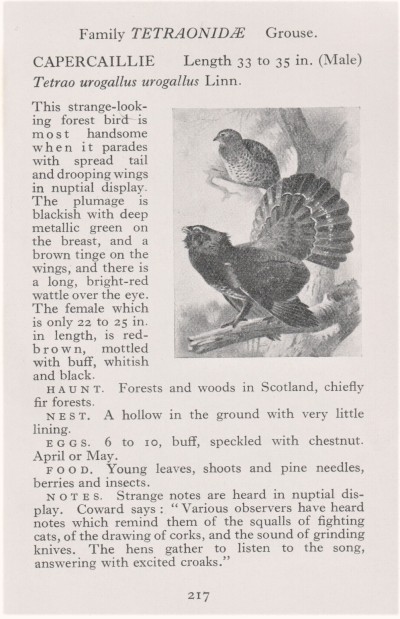

The book is laid out in family groupings, for example Corvidae – Crows; underneath is the specific bird’s name, both common and Latin, with a picture in either colour or black & white. There follows a description of the bird, then five headings of Haunt; Nest; Eggs; Food and Notes (song).

There are 262 listings in the Index. Some of the local names made me smile such as Thick-Knee for the Stone Curlew and Sea Swallow for the Terns as well as Storm-Cock for the Mistle Thrush ‘which perches on a tree and sings into the teeth of a gale.’ I discovered that the Reeve is the female name for the Ruff and Tom-Tit refers to the Blue Tit or Titmouse as this family is rightly called.

I love the description under ‘Notes’ for Capercaillie during courtship: ‘Various observers have heard notes which remind them of the squalls of fighting cats, of the drawing of corks and the sound of grinding knives.’

Under Hoopoe in the description Miss Benson writes: ‘The Hoopoe is a bird of passage and would be more common if it had not been so often shot by collectors. This persecution has prevented its nesting regularly in England.’ She also states the Yellowhammer as being a ‘very familiar bird’; sadly we know today, due to the change in farming practices and other global changes, that this is no longer the case. The same applies to the Turtle Dove: ‘most common in England.’ One of the only places this bird is on the rise is at Knepp Estate in West Sussex where they have ceased intensive farming and have let nature take the lead with the help of large grazers and browsers.

On the other hand, some birds of prey are described as rarities that due to re-introductions are now increasing in number such as the White-Tailed or Sea Eagle. The Red Kite is not mentioned at all but is now thriving. Cranes and Storks are now being helped back into our landscapes, having been absent for hundreds of years.

There is so much more to this undeniably useful little book than first meets the eye, I thoroughly recommend it for both the amateur bird-lover and the ornithologist.

Contributed by Rosemary

(Published on 14th Aug 2022)